50. Black Panther: Wakanda Forever

Rest in peace, Chadwick Boseman.

There’s no way to follow-up such a loss.

And yet, the Black Panther cast and crew did it with grace. They didn’t have to pretend, because they really are a second family in mourning.

Ryan Coogler (writer/director) re-wrote the entire movie so that Boseman’s passing was not brushed off. And Angela Bassett (mother), Letitia Wright (sister) and Lupita Nyong’o (partner) channel their grief to convey three people having to continue living their own lives, while honouring the legacy of such a loved one.

Angela Bassett, in particular, is a tour de force. She is totally believable as a mother destroyed, and a Queen of a susceptible/attractive country in a power vacuum.

I also would like praise the new entries to this world. Tenoch Huerta as Namor, and Talokan an ancient civilization of underwater dwelling people.

Both Huerta, as an anti-hero, and the Mayan inspiration of Talokan are fully humanized, and are also rendered through some inspired choices in production design. Particularly the underwater scenes, which were lit not to look beautiful and welcoming, but realistic and dangerous for normal humans, making you respect even more the adversities Mayan people had to endure.

What doesn’t help these subject matters is the Marvel of it all. The filmmakers did the best they could to make this feel like a standalone story. But, there are still too many moments of ‘Cinematic Universe’ shenanigans that add nothing to the overall themes here in focus, and only serve to distract and dilute emotional resonance.

Still, huge respect for everyone who said ‘yes’ to this project.

49. Belle

“How can we find one person from 5 billion members?”

A reimagining of Beauty and the Beast as an allegory for the pros and cons of the digital world? I would have never thought about something like that.

That’s why we need Japanese animation.

Another reason why we need Anime is the ending of this movie. Holy moly, I didn’t see that coming. And I’ve already watched a fair share of unconventional anime in my life.

Maybe that shock says something about the other 2/3rds of the film. They are a bit disorganized, to the point that they numb you (probably by design, but it doesn’t fully work). Yet, that doesn’t retract from the execution and resonance of the final sequences. Particularly, when a movie is juggling and trying to land such complex topics.

I really appreciated how the movie is not didactic about the Internet and social media. Through visually striking contrasts, it showcases the digital as a human place, where introverts can find a home for their goodness and talent, while having to reconcile with an even more fleeting environment in sustaining an oeuvre.

Despite feeling like the beginning and the middle of the movie are trying to say too much, there was a kernel that got me: fame is faster, but (or and) you need to follow the same type of human-fabricated rules you have in the real world – hierarchy, segregation, prejudice or even imposed order by economic interests.

How do you really have an identity in a world like this? That’s the question the film proposes and resoundingly answers in its final act. Because, online is also a place where you can be emotional.

I’m writing these lines and tears are coming down my face because I’m doing so with the soundtrack accompanying me. The crescendo of the main theme (心のそばに, Lend Me Your Voice) happened to be playing at the precise moment when I landed on ‘a place where you can be emotional’.

It probably is another positive of this movie that I’ve yet to say something of its two most competent elements: the visuals and the sound.

It’s not surprising that the animation is top tier. But, even for Japanese standards, these visuals are pretty special and even cutting-edge.

And the core of the movie is Kaho Nakamura. Without extending her talent to the voice of Belle, the tone and impact of it all wouldn’t be the same.

48. Saloum

No cultural appropriation here.

True African movie. With African cast and crew. And interested in telling an African story, where both the continent’s folklore and vistas inform the cinematic decisions, instead of being exploited as exotic ornamentations.

The cinematography is good-looking without deifying Africa. Only someone who knows it can show us her true nature.

There’s a sense of place in Saloum. More than being a real region in Senegal, the movie, through its character development and narrative trials, makes you sense the distant and close history of this land and its people.

This lends substance to the purpose of the movie. But, let’s not discredit style, when credit is due.

What a stylish approach to tell this story. Not only through the camera movement and flairs, but also in how these characters carry themselves and tackle the problems the world throws at them.

Speaking of plot devices… The third act introduces horror elements I was not expecting. Not entirely sure they gelled cinematically, but I never thought they were out of place from the worldbuilding and allegorical points-of-view.

Instant cult classic, coming from a cinema culture we all should mobilize to know better.

47. Catherine Called Birdy

“Old World Problems. New World Attitude”.

It’s definitely a trend in period pieces nowadays, and I don’t know what to think of it.

So, let’s talk about the movie on its own terms.

It works. The modernization doesn’t feel forced in the writing, and the actors embody that screenplay in ways that never take you out of their old world.

I know Lena Dunham is a bit of low-hanging fruit for criticism these days, but this direction and narrative sobriety with punch is pretty undeniable.

46. Sundown

This film is worth it just to see Tim Roth not overacting.

Then a slight discomfort starts to settle in. Good discomfort. The one that meticulously transitions to tension.

And then the movie doesn’t fully deliver on the build-up of the first two acts. Yet, the fact that it makes you think that it can go to a certain place is a merit on its own. Because that would be a very bold ending.

It’s still worth the ride, since the underlying restlessness is not on the tempo we are accustomed from thrillers. A patient movie that rewards patience, even if not with the release you need by the end. And maybe that’s the point.

Iazua Larios and Charlotte Gainsbourg are also very good and nuanced in it.

45. Argentina, 1985

The subject matter is enormously important. It’s the movie that is not breaking any new ground.

It’s a courtroom drama, where the proceedings take centre stage.

I’m not usually an aficionado of this subgenre, but I have to admit Argentina 1985 is trying to add a few dashes to the formula.

For starters, the movie cares for image quality and photography. The overall aesthetic navigates well the two main themes of the story: 80’s hopefulness, and the tension of horror still personified by the fascists who stalk and predate.

This contrast and Ricardo Darín (portraying the main prosecutor) are the standouts of the film. And they are in conversation with each other, because Darín also plays it dually. On one hand, he is self-serious man, haunted by his past. On the other, he is channelling his knowledge and charisma to teach and inspire the next generation of Argentinians to do and demand better.

I don’t think the movie is strong at conveying the weight and terror of the dictatorship. It has two worthy scenes – in the middle and the very last one.

However, I can appreciate the filmmakers focusing more of their lines and lenses on the youth and optimism. The fact that humour is a throughline in all of this movie says something about Argentina beginning to heal.

Yup. A courtroom procedural with horror and humour elements. Gotta respect it.

44. Bodies Bodies Bodies

The idea of combining whodunnit with horror movie is creative and potent.

The execution here is as symbiotic as it is indecisive.

All in all, the use of dark rooms as stage setting, while the mystery and gore escalate still work, since it makes you think anything can happen.

And, even if the resolution is not over-the-top, I like how it tells on itself and makes you laugh thinkingly on cell phone culture.

If nothing else, watch this movie for Rachel Sennott and Myha’la Herrold. They are stars in the making.

43. Official Competition

The satire here about the cinema industrial complex is well built.

Oscar Martínez and Banderas casted to portray the tension between art and commerce is self-aware to a point I must respect.

However, I prefer parodies that catch me off-guard and are not so on-the-nose.

Banderas is a bit type-casted as the ‘villain’, even if he has a knack for it. After Dolor y Gloria, I’m ready for more explorations of that other side of his.

Penélope Cruz, differently, is the reason to see this movie. One of the most interesting works of her career, precisely because it is very different from her roles in Spanish cinema: enclosed mysterious woman, or everyday woman in touch with her inner anger and tears.

Here, she is completely loose. Without ever crossing to overacting, you feel she is having a blast playing this character, and you can’t help not to have a laugh alongside her.

42. Cha Cha Real Smooth

How things change in one year.

CODA wins Sundance, gets its rights bought by Apple for a record fee, and wins Best Picture at the Oscars.

Cha Cha Real Smooth wins Sundance, gets its rights bought by Apple for a record fee, and nobody is talking about Cha Cha Real Smooth.

I’m not saying that we should be talking about it on Oscars terms. But, since these two movies are in somewhat the same subgenre, and the second has better craft than the first, I would’ve expected something in between best-of-the-year and total-silence.

For real, Cha Cha Real Smooth is a very well done movie for a romantic dramedy. Cooper Raiff, who wrote, directed, produced and acted on it, enters immediately in my mental list of “creatives I’m curious about their next project”.

He is doing it on three levels for me: cares about image quality (this film has amazing cinematography for its scope); cares for themes (toxic masculinity and youth angst are not showcased through melodrama, he simply proposes the alternative); cares for rapport while acting (you never feel he is using his movie to highlight his acting chops).

That’s what this movie is about: caring. And how seeing that as mushy is the real lame.

Dakota Johnson is a star, by the way. I feel like she got stained after Fifty Shades of Grey, and the film industry should be better than that.

41. All My Friends Hate Me

One of the best depictions of THAT guy that tries so hard to impress the most import people in his life (or so he thinks) that he ends up absorbing all the air in the room, and not give them time or space to also be people in a moment.

Casting Tom Stourton was smart. Because his height adds a lot to the imagery of it all.

The film has a slight atmosphere of thriller/horror, which works, even if it never capitalizes on that (seems like a trend this year).

Dustin Demri-Burns is always distressing, though.

40. The Tale of King Crab

A cinematic fable on waiting all our lives for an excuse to leave our routines and vices, only to find ourselves with other routines and vices to maximize the chances of finding that treasure at the end of the epic adventure.

The cinematography of this film is aesthetically perfect at mixing dream-like with real fabric, contributing also to the hope that such adventure is possible.

And a shout-out to Gabriele Silli, who literally carries the movie on his back. Italian performers deserve more credit. They’ve been delivering some of the best acting in recent years.

39. God’s Creatures

A very dexterous script.

It takes the tone and the myths of ghost stories and melds them aptly with the inner ghosts (past and present) of real people in real communities. Even the smallest community: mothers, sons, fathers and daughters.

Emily Watson is the anchor of this movie. Her information is your information, and you can’t help but judge. And that’s what the film is challenging you (and her) on.

This is my favourite Paul Mescal performance of the year. And that’s saying something, when he had a better one in Aftersun. But, I love how the filmmakers are suggesting him to go against type, resulting in one of the scariest villains of the year, with zero overacting.

38. Bones and All

Caution: this is a very graphic movie.

Concurrently, it is also very beautiful.

It is beautiful from a technical point of view, with some of the most stunning landscape photography of the year. And it is beautiful from a storytelling perspective, where you really believe that love did set these characters free.

These two elements – the vistas, and the cannibals on a road trip in them – are what make the premise of the plot make sense. You understand that Luca Guadagnino is aiming his camera at societal segregation. And, even if I preferred a less uncomfortable vehicle to take me there, it works, while the discomfort challenges me intellectually, because the two lovers are written humanely.

There is a commentary here, where the vistas go as far as the eye can see, and these two people don’t seem to have a place to settle. Only when they truly notice what they have in front of them – each other – is when we get shots of ‘magic hour’ in the prairie.

Pink was never as lovely as this.

This uneasy movie is so well written that you might even find compassion to give the villain portrayed by Mark Rylance.

37. Triangle of Sadness

If I didn’t know that Ruben Östlund is very good at subtlety, I wouldn’t have liked this movie as much.

My interpretation for the total avoidance of nuance lands on the possibility that the obvious is in itself a nuanced commentary on the obvious we, as a society, don’t seem to want to engage with.

“Why are you fucking laughing? This wealth lopsidedness is real! And it’s a fucking insult to our so-called intelligence as a species that, in the 21st century, there are still people with this, and people with close to nothing…”

To create a movie out of that paraphrased exasperation, Östlund divided this screenplay in 3 acts.

The first one, which seems like an appetizer in real-time, ends up being the more poignant in retrospect. Money is more social signaling than true human value.

The second act is where all subtlety is thrown out of the window. It makes you laugh. But, remember, there’s a reason for this foxy writer/director to be extracting over-the-top comedy from these over-the-top people. It is indeed shrewd to capture the beauty of a 250 Million Dollar Luxury Yacht in crooked frames, thanks to the true power of the sea.

Beauty as currency, or currency as beauty… No matter what, we all serve our mortal bodies and nature.

And this takes me to the third, and final, act. The titular Triangle of Sadness. A play on the Bermuda Triangle and Lord of the Flies, where all the luxuries disappear, individualism gets eaten by other animals, and we, as a society, as a species, only have our morals and emotions to survive, govern and raise ourselves.

I prefer when Östlund is more understated, but this movie is an instant cult classic.

36. Babylon

When I first watched the trailer for Babylon I was a bit disappointed.

Since Whiplash I knew Damien Chazelle had *this* in him. But, what made me excited for a new Chazelle picture was noticing, in La La Land and more in First Man, a tendency and confidence in not needing to be maximalist to affirm himself. An urge that is patently present in this new generation of male directors, who grew up with Scorsese, Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson.

Babylon is Chazelle’s. No doubt about that. It has his signature all over the place. But it is also Chazelle’s Wolf of Wall Street, Chazelle’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, and Chazelle’s Boogie Nights.

This ended up not bothering me as much as I anticipated. Firstly, these are great films to defer to. Secondly, and more important, Chazelle doesn’t limit himself to homage. He goes wide and beyond. As a matter of fact, the first hour of Babylon is bigger and bolder than any sequence in the three movies I cited.

Consequently, this determination to go louder than the masterworks also brought about more flaws than in all of his previous films combined.

I don’t mind. I respect imperfect results, if the methodology preceding them is sound and courageous.

Like I said, the first hour is spectacular. It is non-stop worldbuilding and style. The second hour is, by design, a lot slower. It worked for me, because more than filmically and rhythmically expressing the slow downfall of a giant (silent film to “talkies”), it contained an alluring inquiry by Chazelle if silent was more artistic than the engineer-centric sound films.

And the third hour is the more experimental. As such, it is where he fails more. Yet, he lands the plane. Not only he manages to establish a biting symmetry with the first hour – Hollywood makes you look like the most beautiful dish ever, engorges itself from it, and then spits you out –, but also envelops his message on a soothing Malickian climax: “Is it worth all the blood, sweat and tears?”

Like in previous Chazelle movies, his answer is a resounding “YES!”. Not sure I agree with him, but it sure is the most magical place in the world.

35. Turning Red

Yes, the Red Panda is an analogy for a girl’s first period.

Simultaneously, it’s much more.

Turning Red is not one of Pixar’s most breathtaking or enchanting releases, but it’s resonance as an empathy machine is up there with some of the studio’s best.

Of course the animation and its sequencing is flawless. Still, that’s not the only reason you come to Pixar movies. And the secret sauce is here.

They really nurture their writers and give them a platform to use animation as symbolic storytelling of the BIG little problems of our lives.

I was never a teenage girl, but this movie made me retroactively understand better the struggles my girl friends went through when I was a teenage boy and didn’t pay attention, and, if one day I end up being a father, uncle or grandpa of a teenage girl, I feel I’m a little more better suited to listen and help her.

That’s why movies like these are so important. Through the common language of animation, children and parents get to see each other in a new light.

I never cared for boy or girl bands when I was a teenager. But, I have to admit: this movie captures that subculture spectacularly. The fact that the climax of this story uses the power of pop music as a plot device is one of the best realized sequences of the year.

34. Kimi

Coincidently, the last Soderbergh movie I liked as much as Kimi was another one with connections to the COVID-19 pandemic – Contagion, more than ten years ago.

All this to say that I’ve been out on Soderbergh for quite some time. I know he is very prolific, but I am of the opinion that his films have been decreasing in quality the last few years. Maybe it’s not a coincidence with him deliberately renouncing big planning and design in order to have a more agile production pipeline. Maybe all that pumping out has a trade-off on polish.

Not Kimi. It’s still not one of his most carefully crafted works. But it’s good!

Kimi is not a pandemic movie. It lives in a context of the pandemic, like us, and juxtaposes it with the supply and demand opportunity crossroads we’re at with digital technology.

When maintaining, or even increasing, convenience can be a gateway to be in transactional relations we don’t fully comprehend. And the most striking aspect of it all is this not being one of those movies where the AI goes rampant.

The film is, above all, a thriller. As such, you’re counting on a third act climax. Let me tell you, I was not counting on that. And Soderbergh movies are known for their nice twists. Zoë Kravitz is incredible throughout, but in those last 20 minutes she shines the brightest.

And, where has this Rita Wilson been for all of her career? Very strong and shady supporting performance.

33. Flee

When people say that “animation is for children”, recommend them Flee.

This adult person needed animation to tell his very real and tragic story.

I never saw the animation medium resorted to in this way. It’s because it’s animation that you feel the pain in this documentary more intensely.

A Documentary!

A genre where we expect intensity and human connection coming from ‘real’ photography. I tell you what: it doesn’t get any more real than this.

You feel in your skin that the only way this person would make his catharsis and talk to a camera was if his head was characterized.

The only way he could see the visual storytelling of his past was through the colouring of animation.

Human emotion is real, no matter the medium conveying it.

32. Emily the Criminal

On the verge of the cheeseburger subgenre of movies: the “Garbage Crime”.

It has the structure of a cheeseburger movie, but it treads on riskier flavours.

Not only is it grounded in a relevant premise, but it also ends on a quizzy proposition.

Good garbage crime movies like this one are supposed to be watchable with your brain turned off. Not this one. You will question the morals of the film, not because they are necessarily bad, but because they are intriguing.

Our culture taught us that theft is one of the capital crimes. Be that as it may, who is robbing who?

On other note: finally, Aubrey Plaza can showcase her depth, by not being typecasted to play the hag.

31. The Souvenir Part II

I have to admit: I didn’t fully grasp the meaning of the final sequence of this film.

And, without trying to relativize my shortcoming, maybe the point of that sequence was not to be fully grasped by another. Maybe its greatest strength comes from being so personal to the writer/director.

That was what made me fall in love with The Souvenir ‘Part I’ back in 2019, and that is what continues to captivate me in Part II.

In an age when filmmakers are being more upfront about, and putting into film, the inspirations and traumas that nudged them to want to make movies, Joanna Hogg shows us a semi-autobiographical world for whose events can only be truly ingrained and begin to be understood through art.

“People don’t talk like this”. Yes. People don’t talk about this stuff. Only art can.

30. Jerrod Carmichael: Rothaniel

Perhaps there’s an element of voyeurism in this.

I never felt it.

Carmichael is so logical and fluid in going through the gamut of emotions that I felt more part of his support group than audience.

It is a comedy special. Even so, it is the performance that allows him to be non-performative about one of the most important moments in his life: coming out as gay publicly for the first time, while deconstructing the why and the why’s relation to his upbringing in a toxic (to say the least) family environment.

I laughed, and I cried, and I laughed again.

29. Fire of Love

«A set of forces collide inside the planet, throughout the enormity of geologic time, to trigger one instant, an eruption, that forever re-shapes the Earth.

And across humanity’s two million years, two tiny humans are born in the same place, at the same time, and they love the same thing.

And that love moved us closer to the Earth.»

28. The Menu

Triangle of Sadness (Palme d’Or winner), Glass Onion (sequel to Knives Out), or even White Lotus (TV series)… Just to name a few recent examples. What do they all have in common?

A boiling point we’re reaching in the history of the Northern Hemisphere (Western Society, if you prefer), after 200 years of Capitalism, when reverberating evidence lays bare that the socioeconomic paradigm truly in force is: oligarchy for the rich, individualism/liberalism for the middle and poor classes.

For example, in the two years to December 2021 (pandemic at full throttle), the richest 1% on the planet (and not the companies they work for) bagged up nearly two-thirds of all the wealth created by the WORLD economy.

The Menu is the best 2022 audiovisual statement about this aspect of our lives, and a cinematic parable on the increasing wish for a post-capitalism: rethink it, and restructure it.

Textually it picks up on the current fascination apparently people have for cooking shows with “charismatic” chefs, and sub-textually destroys the hypocrisies (and stupidities) of modern capitalism/neoliberalism as different phases of a degustation event.

It is Mark Mylod (director), showrunner of Succession, using the higher probability of the one-sitting in cinema, instead of the ‘one-more-episode’ of TV, to be truly biting and defiant of the audience’s trained acceptance of sacred cows like “economic growth” and “meritocracy of the ones who truly strive for perfection”.

27. Hustle

It’s because I love basketball and the NBA that when I recommend a movie about such subject matter you know I’ve been especially vigilant of flaws and inconsistencies.

This is legit. It is well-founded as a sports movie, and it has a reason to be as a drama.

The basketball is cinematically played like the one that lives in your head. It helps that this was produced by LeBron James and he convinced his peers to be in the major action scenes of the film. But, Juancho Hernangomez and Anthony Edwards are good in this beyond basketball. “Ant-Man”, in particular, has a career in Hollywood if he wants.

And, of course, Adam Sandler, who, without him and his love of basketball, this project wouldn’t have worked. This is the best type of “Sandman”. Sad, angry and introspective, without losing the timing and acidity of his humour.

Ben Foster is, as usual, proficient at portraying an abhorrent son of an NBA franchise owner.

And to note that this film has way better cinematography than these productions usually care for.

I love that the signature play of LeBron’s career is the block against the Golden State Warriors in Game 7 of the 2016 Finals, and this movie, above any other move in basketball, uses the block as a plot device and something to cinematically romanticize about. Can’t be a coincidence xD

26. Prey

Please, producers, keep greenliting Dan Trachtenberg’s ideas. This young writer/director doesn’t miss.

On a first passage, this premise seems to have holes in it. Then, you understand that the poking was intentional, and Trachtenberg uses them expertly to raise the stakes of everything.

This is the best Predator movie since the original design. It takes the rules of the fiction and brings them to a place of ludic resourcefulness.

Amber Midthunder is a revelation. And not for a second was I taken outside the movie to question if she was going to be able to solve this problem. This is done, like I said, through meticulous screenplay writing and staging. But also through her acting charisma.

The action set-pieces were so astutely choregraphed. Them being creative resonates with her having to go much more brainy, and hunt in a different way, to establish her place and be respected in a world of men. Work better, not harder.

It’s always so much more fun when our heroes outsmart, instead of brute-force, the villains.

I also respect this production for going with an all-native American principle cast. More often than what makes sense, these blockbusters can’t resist putting white faces on the poster.

25. A Hero

Asghar Farhadi is one of the greats.

In A Hero it becomes again patent how observant he is of the human condition. Flaws are not bastardized as simple objects of study. He writes them and explores them as dynamic side effects of human interaction, like social signalling or social constructs (family, business partners, law).

The judgmental angle of interaction seems to be of interest to Farhadi. And, since his stories come from human nature but are not hyper-real, he can push and pull outgrowths like flaws, virtues or instinctive reactions.

By testing how interiorizations can (or cannot) be manifested as by-products of interaction, he tends to land on narrative textures that feel very relatable and in conversation with our own lives. But not preachy.

Amir Jadidi, playing the titular hero, is a good example of a ‘Farhadi-an’ character not being delivered as a vessel for human analysis and didacticism. He is the opposite of prototypical. A mystery box, because we don’t have to fully know a person to engage with the manifestations (or lack of thereof) they impart on the narrative world.

You know this is a magic trick, where writing, explorative directing and performance come together to create a non-hyper-real person who is testing and being tested by seemingly immovable human structures and seemingly unpredictable human emotions. Yet, it’s all very captivating.

If anything else, this is too much of a ‘Farhadi-an’ movie. Which is a non-problem, because, like I said, Asghar Farhadi is one of the greats.

24. X

“Elevated Horror” is a bullshit concept.

Movies either execute on their ideas, or they don’t.

I bet no snob would call Texas Chain Saw Massacre meets Pornography “elevated”. And yet, X executes better on its human commentary than most non-horror movies out there.

Here, Ti West, the writer/director, doesn’t bring dissonance to his worldbuilding just to be elevated (where you have the land of horror here, and the land of ideas there). No. Body horror is the commentary.

The fact that the fleeting nature of beauty and sex appeal is the monster in this movie only makes it more palpable and piercing, because you know that she’s also waiting for you sooner or later.

I also appreciate how this film, through that carnal lens, disarms a lot of the hypocrisies our society “elevated” in regards to the sex industry.

Mia Goth is unbelievable. One of the best performers of 2022.

23. White Noise

«Jack Gladney, a professor of “Hitler studies” (a field he founded, though he has never taken German classes), who’s been married five times to four women, lives with Babette, his current wife, and together they raise a blended family of four children, and both are extremely afraid of death.

Their lives are disrupted when a cataclysmic train accident casts a cloud of chemical waste over their town – “The Airborne Toxic Event”.

Later, everything has returned to normal except for Babette, who has become lethargic and emotionally distant from Jack and the rest of the family. And, through quarrelling and conversation, their respective fears of death become exacerbated, for different reasons (or not).»

I mean, White Noise, the original book, was published back in 1985. But man, it doesn’t get more current than this, huh?

The way this story connects crowds for Hitler or Elvis to lines in the supermarket or traffic, and all forming a net of ideology for us to lay down our fear of death, is genius.

I don’t care that the movie has some pacing issues. It looks like a million bucks, it’s completely out-of-the-box for this director (Noah Baumbach), and it’s adapting high concept to images. I want more and more films like this.

22. The Batman

This is the best Batman.

Not the best Batman movie (that’s still The Dark Knight). But the best Batman characterization we’ve ever seen on the big screen.

Aesthetically, this film is as accomplished as the Nolan ones, with its own take and identity. The cinematography by Greig Fraser is some of the best of the year (which is not a surprise), finding a masterful balance between damp darkness and blazing hopefulness. The music by Michael Giacchino is also some of the best of the year (this is a surprise, because I always find Giacchino’s scores too formulaic and preoccupied with being pitch-perfect), finding its soul in the ruggedness, uneasiness and muscular atmosphere of Gotham.

All the actors are great. I already know Robert Pattinson is skillful at interiority. I didn’t know he was this good with physicality. Zoë Kravitz, like Margot Robbie says in Babylon – you don’t become a star, you are born a star. Colin Farrell understood the assignment, and is having a blast playing The Penguin. Paul Dano is the master of uneasiness. And even John Turturro raises the characterization of Carmine Falcone, making him more menacing than he’s ever been.

Finally, Matt Reeves (writer/director). By taking inspiration from Se7en, he tricks us into thinking that this Batman, like the Fincher movie, is emo nihilism. And then the dexterous twist comes. After nights of rain, bleakness and terror, the red sun comes in the new morning, making this one of the most uplifting superhero movies ever.

They film Batman actually being a hero to the people of Gotham. Boots on the ground, saving the common folk. That’s interventionalist grunge, not emo.

21. Licorice Pizza

I honestly don’t know what this film is about, apart from the foundation of a tried-and-true coming-of-age story on finding your place in the economy of work and relations.

Nevertheless, he always gets me. Paul Thomas Anderson keeps finding a way to completely immerse me in his worlds. Whether it’s a porn set, an oil-drilling site in the arid desert, or the San Fernando Valley in the midst of cinema revolution in the 70’s, I always want to be there.

The tone of his movies, through image and music, and not interested if the renditions are realistic or not, always put you there. And then, through screenplay and editing, he makes your body and brain be in the rhythm of his characters and their actions.

It’s in the combo of technical with storytelling, and how he maximizes each without ever straining the partnership of the mix, that we feel the flavour of the place. With it comes the sounds, the smells, a certain type of light, the touch of a room…

Suddenly, you’re there. And, for better or for worse, you don’t want to leave.

PTA is really good at making movies and movie worlds, even if it’s difficult to pinpoint what makes him good at it.

This time, it also helps that Alana Haim and Cooper Hoffman are authentic revelations.

20. Avatar: The Way of Water

Must start by saying that I did not like the first Avatar movie.

I respected it for the technological advances it brought to cinema. And it had ideas. But I never felt them. The 2009 work was Cameron the engineer at his best. Cameron the artist nowhere to be seen.

The Way of Water inverts the ratio.

It is again a benchmark in engineering, especially for a current era, when technology is impressing us at slower rates. Yet, it is a good film because it channels those techniques in service of something. Your senses are heightened not because of the audio-visual spectacle, but because your emotions connect with the soul of the movie.

You can’t be cynical of the existence of this sequel. Of course, it will make a LOT of money. Notwithstanding, it is patently obvious that this second movie was created because Cameron really loves this world.

More: what makes this even commendable is how you feel Cameron’s mission to say something about our own natural world through this passion of his. It might seem odd to call Avatar The Way of Water auteur cinema. But it is. Not only because no other filmmaker does it like “Big Jim”, but, more importantly, because you really feel his soul connected with it.

Honestly, the second hour of this film could be an entire nature documentary with no dialogue. The relationship that it establishes between a Na’vi teenager and a Tulkun (whale), without a common language besides naturalistic connection, is one of the most beautiful and poignant sequences of 2022 cinema.

The film would be even better if it had doubled down on this Malickian style. But we know Jim loves his action set-pieces, villains, and has a Stockholm syndrome-like affair with guns and explosions.

Don’t get me wrong: the third act works. Cameron DOES know how to shoot climaxes, and his knowledge of the sea helped in creating a powerful contrast of water as both beautiful and dangerous.

And yet, you can’t help but feel that those plot machinations are only there to make this movie reach the biggest of audiences, to pay for the slow-paced minimalist scenes (that are the TRUE purpose of the director).

Immersion breakers aside, had you asked before me experiencing this film if I was interested in a THIRD Avatar story, I would’ve said No.

Now I am.

19. The Northman

Western culture has a bias towards 2 or 3 templates of storytelling.

The majority of those come from Shakespeare, who, in turn, had a bias for the Bible.

Hamlet is one of those stories. Even The Lion King is pastiche of that.

Thus, when a ‘new’ piece of artwork presents itself so conspicuously formulaic, it’s only natural that we question our need to experience it.

Do not worry, this has originality. As a matter of fact, this is THE original story. Not only are Robert Eggers (writer/director) and the poet Sjón telling the story that inspired Hamlet itself – the tale of Prince Amleth –, but they are also singing it in their own timbre.

Believe me, The Lion King was never going to have a twist in the third act like this. The Northman, with its powerful ending, is in itself questioning and sending a message about our own Western culture, and how it was shaped by stories like Hamlet.

The only problem with this movie is that the cinephile at Focus Features that decided to finance a Robert Eggers joint has a boss. If you decide to support the work of such a quixotic filmmaker, you know that you should let him have final cut. Apparently, the boss of the boss didn’t understand that, and you feel the studio notes.

Nevertheless, this is for the most part an Eggers proposition. His interest for how the faithful recreation of the real clashes with myth is palpable everywhere. The cinematography, for example, has Scandinavian haziness without concealing the whim and supernatural of Viking lore.

He knows he shouldn’t (and can’t, to be perfectly honest) obscure a force of nature like Alexander Skarsgård in this movie, so he owns it and makes it bombastic, without ever losing focus and interiority.

Even Nicole Kidman is doing epic like we haven’t seen her do for ages.

And Björk is back to the big screen!

18. Decision to Leave

When I first saw this movie, it was the biggest disappointment of the year for me.

Not because I felt that it was a bad movie, but because I had (wrongly) certain expectations for a Park Chan-wook film. You know, the twists and turns of Oldboy or The Handmaiden.

After studying Decision to Leave, this might be the most I am underrating a work of 2022. What does it say about me that, the film does indeed have the thrills, they simply aren’t examined through sex and violence like in his previous works.

More so: Decision to Leave might be one of the most intellectually romantic films ever. And I failed to see that the first time.

I was so hyped for the histrionics that would certainly come, that I even missed another staple of director Park’s filmography: innovation in technique. This is not worse spiritually than missing the point of the movie. But, it’s probably worse tangibly, because they are so many. I mean, how could I? Shot after shot, Decision to Leave is introducing novelty to the industry.

And all that craft is used in service of one of the most ingenious metaphors of the year. I’m not compensating here my lack of understanding there; but, let me just redeem myself by saying that the subtextual story about the Mountain and the Ocean in this film is both incredible and beautiful writing.

I’m sorry director Park.

17. Paris, 13th District

Years ago, movies with eroticism were half supply for a demand without porn democratization, half Freudian bullshit about sex being a misty bubble where we release the killer inside all of us.

In 2022, Jacques Audiard (director) and Céline Sciamma (writer) would never bring erotica back as a power fantasy. Les Olympiades is a district of residential towers located in the 13th arrondissement of Paris. And I really connected with how these filmmakers start by presenting sex as a release from encroaching urbanization and max-structured lives. And then, a twist on their own idea of structurisation…

You might notice the foreshadowing in some visual cues. The camera outside the residential district doesn’t avoid compositions with trees in the wind. Or the moment in the courtyards of Les Olympiades, where its either bright hot sun, or torrential rain.

Our characters, who have been connecting through sex to escape the expectations of over-though lives, start to notice that that same sex is not the same with everyone (Freudian bullshit).

Not that this film is even trying to make a grand statement about love.

It simply is saying: instead of encasing yourself with your plan and expectations, as a defence mechanism against the towering of modern society, pay attention to the people next to you. It may start as noticing a wart in their inner thigh. And take it from there.

Sex is neither a motel room, nor an essential ‘ingredient’ to the relationship formula. It’s human interaction. And, as such, it will always be partly emotional and partly rational, even if we don’t want to see it that way.

16. The Fabelmans

“Movies are dreams that you never forget.”

Looking at my relationship with Spielberg movies in the last 20 years, and that mission statement, I was completely expecting a perfectly well made film, with zero rawness and vulnerability.

I was completely wrong. It might not be his best, but this one immediately enters my list of favourite Steven Spielberg’s (if not my favourite – it’s tough to be objective about the formative ones).

My respect and love for this film comes precisely from it not trying to be a perfect dreamlike fairy-tale. He opens up to us. Not through an exercise in voyeurism to his past and family, but through an immensely more thought-provoking way: without shying away from his precocious genius, he questions if his camera, as a safe space for his timidness, has been more truth-teller or liar.

I never thought I would ever see Spielberg exposing himself this way. This is a level of accountability rare for any filmmaker. Let alone one of our ‘heroes’.

He really is putting through the wringer more than the career choice that gave him so much. The Fabelmans has a scene where he actively hides away his camera, questioning his own passion and identity.

This is a semi-autobiographical recollection, and yet you can’t but see teenage Spielberg in Gabriel LaBelle. Not because he resembles him physically, but because he is extraordinary at making you believe that this kid is the kind of soul capable of one day directing both E.T. and Jaws.

Truly, LaBelle is one of the best young performances I’ve ever seen.

There’s a story beat with a bully that is the cornerstone for that interrogation of the power of filmmaking to either tell or transform reality. And Gabriel LaBelle deals and delivers as complex scrutiny as the best actors that have ever worked with Spielberg.

Welcome back to my heart maestro. There was always going to be a saved seat. But The Fabelmans cements it.

15. All Quiet on the Western Front

Like me, you might misjudge this film at first glance.

You might think: European Oscar-bait. ‘1917’ worked, so let’s take that style and apply it to the 1930 Academy Award-winning story of the same name.

This film has very little to do with the American version of ‘Nothing New in the West’, and even less with 1917.

It is as technically immaculate as 1917, especially if we consider that it cost 5x less. And yet, in contrast to 1917, this film is not interested in using its technical mastery to tell the story of human exceptionalism.

What the 2022 rendition of All Quiet elevates is human darkness. Sincerely, this is more of a horror movie than an epic. Like the war machine, it is relentless in its messaging: there’s nothing epic about death at the hands of another human.

Here, war is not a historic moment from which heroes rise, because heroes end them. Here, soldiers do not matter. And, like a horror movie, that’s very uncomfortable, because we are put in the position of a solder: we don’t matter.

That’s the biggest challenge of the film. Some people may already be desensitized to gore and audiovisual terror. But, it’s always harder to face non-anthropocentric facts about our own lives amounting to nothing more than flesh, bones and dust.

It’s not like the film paints a picture where generals or policy makers matter more. They are the ones responsible, yes. But, there are no larger-than-life figures or momentous speeches here. Just the same matter-of-factness and mission for materialism that explain why there was a 2nd World War right after. And a War in Ukraine, right now.

Amidst all this denseness, an element makes this film stand out even more. To nail its theme of meaningless anthropocentrism, the filmmakers decided to edit in, between the sequences of most destruction and violence, long quiet scenes of nothing but nature.

Nothing? Maybe that’s everything. Since nature, beauty, the planet want nothing to do with our self-imposed problems.

14. Hit the Road

Comedy can carry the strongest of catharsis.

It’s in the farce of comedy that tragedy finds its match, becomes manageable, and finally internalized as something real.

Among many sources of cathartic fun, a child’s chaotic goodness is the tabula rasa we sometimes need to take a step forward in a world that we now see as evil, scary and unpredictable.

Rayan Sarlak, the Little Brother, is the shining sun of this film.

Add to that a screenplay written so that we start with the same information as him, and the movie wouldn’t work as well if we didn’t vibe with this kid’s energy.

As adults, we start noticing that everything is not ok. There’s a danger looming in the air. But, since we spend the majority of the first act inside a car, the closeness of this family is limited to physical.

The subject matter seems to be too painful to address in such a claustrophobic space. Like they are afraid, by talking about it, the monster will materialize right then and there and squish this moment out of existence (no matter how bad the moment is being).

And then, they arrive at their destination. Suddenly, there’s space for each family member to distance themselves from the others. Yet, you find them closer than ever before. Emotions and dialogues become truer and rawer, and you understand the different pain of every single one of them.

Even though I highlighted Little Brother, it should be said that Brother, Mother and Father, portrayed by Amin Simiar, Pantea Panahiha and Mohammad Hassan Madjooni, respectively are all best performances of the year. No archetypal acting in sight. All unique fully-formed humans, with their quirks and sorrows.

Finally, I would like to point out that it’s striking that, during the first act in the car, we have sunny sky with clearly visible landscapes. At destination, the family is closer, but the atmosphere is foggy, in mountainous terrain with no clear direction to take.

Like the director (Panah Panahi) saying: the movie mystery might have been revealed, but for this family they don’t know what’s beyond the veil.

This is one of the most impressive directorial debuts I’ve seen in years.

13. Petite Maman

Even though this is a fantasy premise, the film doesn’t need to be long to explain the rules of its universe, since those are rooted in magical realism.

I love magical realism.

And I like it even more when the fantasy elements aren’t overexplained. When the story is more focused in trying to make us remember a feeling we can’t quite express within the rules of our reality. But which we can begin to shape through imagination, and then ourselves try to actualize in our own lives.

It’s through the power of imagination that we become a better species. A better people.

Petite Maman introduces children to the concept that their parents were once children like them. And it tries to make adults remember the feeling when they, as children, might have thought of their parents as equal human beings.

This film is much more than the idea that we should never forsake the child within ourselves. Céline Sciamma (writer/director) is genuinely interested in the morals of children as something we should make real in the conduct of human relations.

Childishness, naiveté and playfulness should not be so easily used as pejorative terms like our society seems to has decreed.

12. Broker

Hirokazu Kore-eda might be the living director better in touch with what makes human beings good.

We’re talking about a serious subject matter, a cast of unsavoury characters, and heavy drama pervading their decision-making.

And still, Kore-eda never directs Hong Kyung-pyo (the cinematographer) to avoid clear skies or Jung Jae-il (the music composer) to not be pleasant to the ear.

There’s a hopefulness in Kore-eda’s filmmaking that in other directors’ hands would feel too allegorical or even manipulative. His signature gets you because he isn’t content in just throwing hope and optimism to the future.

He chooses to be in the present with his characters. And, by doing so, he has to contend that not only are they flawed, but will probably be in conflict with each other. That’s the secret sauce.

From bad decisions, planned actions to hurt, or simply humans having to come to terms with the consequences of their own passiveness or instinctual morality, there’s always a blip of human goodness in there.

Kore-eda is not trying to make a grand statement about what is a good person and what makes one good. His craft resides in using the camera to focus on that smallest of blips, amidst all the murkiness of complex social contracts and behaviours.

11. Happening

Based on the 2000 novel of the same name, by 2022’s Nobel laureate Annie Ernaux.

This is the most important film of the year.

More urgent now that we witness so-called “First World” countries, like the USA, overturning the constitutional right to abortion.

Some people call it a retrograde step of 50 years.

This film, myself here, and many, many, many other women throughout history question: why only 50 years?

10. RRR

The film event of the year.

If we look at the list of highest-grossing movies of all-time, it becomes clear that something started to happen around 2012. Disney bought Marvel in 2009, and started testing the possibility of a Cinematic Universe with a Phase One that trial-ended in 2012 with the great commercial success of The Avengers. By 2013, we were already having sequels to Phase One movies. In that same year, also Disney concludes the acquisition of Lucasfilm. Two years later, we witness the start of the same kind of formula with Star Wars The Force Awakens. In parallel, we realise that other studios are adopting the same ethos: 20th Century Fox decides that Planet of the Apes is also a franchise, and Universal Pictures is ready to have another go-around at Jurassic Park.

RRR is BOLDER and BETTER than all of these movies. Which makes me say that it might be the film event of the decade.

Contrary to what Martin Scorsese said about ‘theme park’ movies, I recognize immense cinematic merit in people cheering Captain America being worthy of Mjölnir in Avengers Endgame – that’s the same human connection all art strives for. But, audiences, with no relation or build up to Indian culture, getting out of their seats to go in front of the screen to dance Naatu Naatu in the middle of RRR? That’s on a whole ‘nother level.

Hollywood blockbusters could learn many things from RRR.

The first, and most important: care for saying something outside of yourself. Many movies have been made about the struggle and fight against European colonialism, but I have never seen one come out so substantially victorious.

And it comes out winning, because – second lesson –: it is more confident than self-serious about it. As a European, I connected more deeply with their suffering precisely because they don’t pull any punches in this film. They had to fight, and intensely they fought. In the end, what you see on the screen is a people both jovially loose and strongly confident with their culture and identity.

You see their tremendous pain. You see them moving mountains to end it. And then, you see them cathartically celebrating their victory. That’s why you are white-knuckling your seat during Komuram Bheemudo, and dancing Naatu in the same movie.

Third lesson: don’t stash anything for a sequel, just to keep nickel-and-diming audiences with the promise of more wow moments. If you have ideas, try them. I never felt the 3 hours of RRR. The film keeps showcasing imagination and creativity in how to do BIG in blockbuster movie-making. Scene after scene, after scene, after scene. Honestly, at hour 3 I was astonished by how they hadn’t run out of new things to show us.

All impressively edited so that the spectacle is always in tune with the outside of itself message of the story.

Fourth lesson: Hollywood big stars, look at Ram Charan and N.T. Rama. This is ACTING. Not overacting. Truly thespian transformation. We are talking about two of the most ‘expensive’ actors in all of India (there was a bet on RRR never happening, because no studio could afford Ram, Rama and Rajamouli – the director). And they aren’t in the slightest preoccupied in guaranteeing a brooding character that cements the seriousness of their careers.

They do rage, inner struggle, muscular action, joyous dancing and bromance. All in the same movie.

Please, if you haven’t seen RRR, do it.

If you have, do it again. It’s even better on a rewatch. I reckon this will end up becoming one of the movies I watch more in my life.

It’s a blast of a journey. ALL of movies into one. The MOST movie.

9. Top Gun: Maverick

Technically, the most accomplished film of the year.

A new benchmark in cinematography, by Claudio Miranda. The sound editing and sound mixing crews teamed up to make your seat thunderously reverberate without masking dialogue. You also have Hans Zimmer, so you know you’re in for some special compositions. Or, Eddie Hamilton, the editor, who assembled an experience that is both a breeze and a white-knuckler.

There’s a sequence, capping the second third of the film, that, if not the best of the year, is certainly the most electrifying encapsulation of the power of the movies. Its arrangement and progression is testament to the ability of non-worded action cinema moving you both physically and emotionally.

Even the screenplay, which many people don’t equate with technical acumen in a movie, is top notch here.

It manoeuvres audiovisual spectacle, between the expectations of a 36-year-old legacy sequel to a popular classic, while challenging itself to carry a new weight of wanting to tell an heartfelt story of not going gently into that good night.

I like the 1986 movie as much as the other guy.

Maverick is a way better film. Not because it has state-of-the-art filmmaking. But, because it has something grander to say.

I was caught completely off guard, by a movie I was solely going for the bells and whistles, when I realised that they were taking the idea that career accolades don’t matter if you’re doing what you love, and cohering it with movie-making and the state of the movie industry itself.

This film is more of a statement on insisting to put a movie through the communal experience of the big silver, and on persisting in an era of non-committed consuming through streaming, than an exercise in nostalgia.

«The ending is inevitable Maverick: your kind is headed for extinction.

Maybe so, sir. But not today.»

Due to the pandemic, and many laureated filmmakers being confined in their homes with their thoughts, 2022 was particularly rich in projects about the collective power of the movie theatre. Top Gun Maverick was the best of them. Not because it brought back the most people, or kept making people leave their houses, and buy a ticket, to re-watch it when they could do anything in the world that night. But because, of all the filmmakers, it was the one who felt more personal, and audiences consciously or subconsciously assimilated and connected with that on a deeper level.

Personal to Tom Cruise.

You know that because you notice that he is not merely rethreading Pete Mitchell. He is not even adding a bit of Ethan Hunt to the action. No. He is summoning back the nuance of the 90’s performances that guaranteed him a place in the pantheon. And maybe something more… A fragility.

And it landed on people’s hearts. To a point that Top Gun Maverick’s strategy, of refusing to release on a streamer, despite it being ready since 2020, and only open to the public when movie theatres were back available, is being considered by both who owns and who finances the digital streaming platforms.

The Dark Knight was probably responsible for the Oscars rethinking its relationship with the general public. Top Gun Maverick apparently just did the same thing in symmetry: audiences rekindling their love for the film industry.

8. After Yang

I am of the opinion that it continues to be vital for stories set in the near future to have a tinge of pessimism. They become indelible snapshots of our culture, warning us beforehand of our own dark tendencies. It’s preventive medicine in the form of memetics.

With that in mind, science fiction can be equally poignant and memorable when optimism is its kernel. It’s tougher to do well, because people are naturally suspicious of utopian tinges.

After Yang, the sophomore work by video-essayist turned film writer/director Kogonada, is one of the good ones. A great one, to be more precise.

For starters, Kogonada is not interested in directing his camera to a larger-than-life utopia. His focus is on how there are some utopianisms that are not only achievable by singular lives, but are also worth questing for.

Even if memory means past, and is a completely different consideration for machines and humans, physical and metaphysical respectively, After Yang proposes that both can contain the clues that make us move forward with a greater appreciation for the real connections we make along the way.

It doesn’t get bigger than Colin Farrell in the early 00’s. But, like reconciling with memory as an achievable utopianism, Colin Farrell as a quieter and more introspective performer contributed to him becoming a better actor. And changed how he is going to be remembered in the future.

This film touched me. A soft touch. Though, one I’ll never forget.

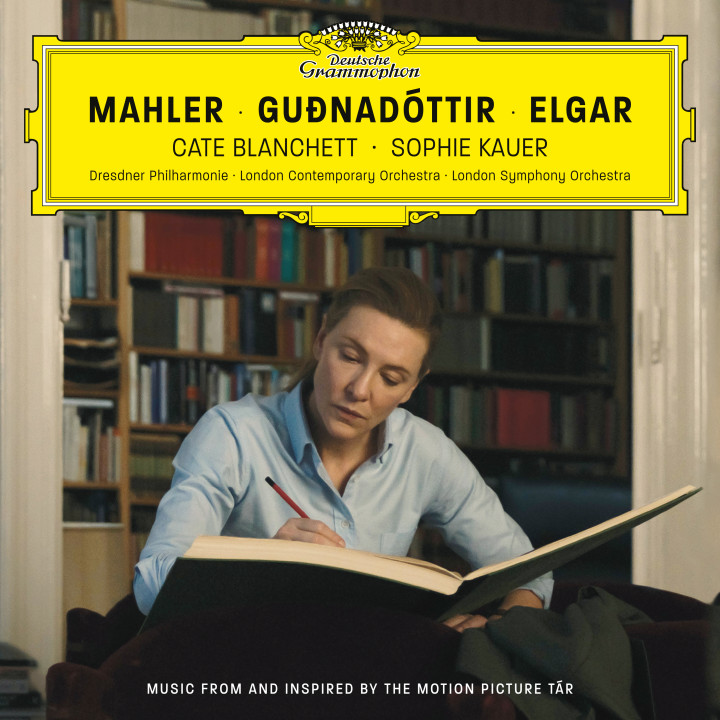

7. Tár

TÁR was my most anticipated movie for 2022, literally because I had no idea what to anticipate.

It surprised me, but not in the way movies difficult to gauge usually do.

The new Todd Field does not surprise through visual motion or narrative twists. Its proposition is special precisely because it’s not “the new Todd Field”. It’s not about a singular vision. It’s more nuanced than that: it questions the notion of a singular vision.

By taking on the world of orchestral music, and its paradoxical fascination with the singular composer (despite the resounding evidence coming from the art of all those musicians in front of the conductor), Tár risks navigating a canon that arguments for authority and contends that only the individual, not the collective, can reach the nirvana of geniality.

This is a film about classical music. Yet, it could as easily be about the corporate world, and its cult for CEO’s as sacred cows. Or even about the film industry.

Opting for a sterile cinematography, with shades of out-of-this-worldness, suggests that they were not targeting precise realism, but universal reality instead.

Additionally, it was not production randomness that resulted in the black screen credits being shared in the beginning, instead of the usual end of the movie. Also, they are presented in ‘reverse’ order.

And that’s Tár. A film that wants to analyse the relative positioning of things, and be there to peruse when that same order is hierarchically destroyed. What art and humanism are there on the other side? Maybe all?

Cate Blanchett utterly disappears into the role. The fact that there are people coming out of the theatre with their phones in hand searching for real-life Lydia Tár – a completely fictional character – is proof that performances like this are way more impressive than biopics.

It’s also completely in tone with the macrocosm the film is trying to reach and recreate that Deutsche Grammophon, the prestigious classical music label, decided the score composed by Hildur Guðnadóttir was worthy of their recording seal.

Finally, the last shot of the movie might rub some people the wrong way. I loved it.

This screenplay doesn’t purport to answer many of its questions. But, for me, choosing to leave such a shaded film in a place of fantasy is answering the above question of: What art and humanism are there on the other side?

Prestige and quality are not synonymous. Whilst prestige plays in the realm of transactions, quality plays with the soul.

6. Everything Everywhere All at Once

Like the title says and intends: you can connect with this film from many different sources. From pain, happiness, or even something in between.

Movies that try to say everything, more often than not, tend to feel very vapid. I.e., they end up not conveying much more than a hat on a hat, so to speak.

What makes Everything Everywhere All at Once exceptional is its approach to that maximalism. Instead of many ideas converging, it has ONE, really strong and important, and your engagement with the message comes from, at first, sensing that something powerful is buried in there, and then uncovering it along the way.

Like, writers/directors, Dan Kwan and Daniel Scheinert said: this is a hat on a hat on a hat on hat on hat. For me, that’s maximalism done right, because you don’t feel pampered to find the answer just below the second hat. The fundamental theme feels more earned and significant because you went on a more active journey to get uncover it.

Like I said: you can interpret this story from many different viewpoints. It was clearly written to be fun doing so. On my first watch, I made sense of it all by perceiving it as a parable for generational dissonance and how to aim for and self-actualize in the land of opportunities.

Everything Everywhere All at Once is the best post-internet film. It doesn’t just comment on the internet. It fully embraces it in all its tonal whiplash: the maximalism of the movie IS what it feels like to scroll through an infinite amount of stuff.

The internet is the land of opportunity where we can assimilate more interesting ideas, aspirations, emotions or experiences, from any continent, in an afternoon binge, than our ancestors in the entirety of their lives.

Even when used for productive tasks, the fact that it is a land of constant evolving novelty that offers a multiverse of answers, for endless real problems, has an effect on how we perceive our own real world, and leads to a tipping point in our minds.

EEAAO is not only talking about the learning and reassessment that comes from being exposed to new ideas or perspectives. It is saying something about the enormity of opportunities we now assume could be ours: alternative lifepaths, measuring ours to others’, a state of non-identity, unable to feel what’s important to you…

And at a certain point, if you actualize on the internet too fast and/or too far, when you are already overrun (but your brain doesn’t know it), a defence mechanism kicks in: ideas, images, aspirations, texts, emotions, videos start to look like a blur.

Cynicism and Nihilism take over. Nothing matters.

In a post-internet era, there is an even bigger generational divide on how people who didn’t and people who did grow up with the internet aim for and self-actualize opportunity.

Michelle Yeoh is phenomenal in capturing and externalizing these concepts and dichotomy. We all know her for being a superb physical performer. Yet, no matter how much she astonishingly fights it in this movie, she comes to the realization that she isn’t equipped to handle this new world.

These fighting choreographies are amazing, and the visual effects are awesome for a 20 Million dollar movie from a crew with very little experience in VFX. All that would also start to look like a blur and amount to nothing, if Michelle Yeoh wasn’t capable and ready to go in the interior of her own self as a performer and person, and come out with the universal message the film intended to affirm from the start:

It’s not slowing down. Our world and human experience are increasingly entwined with the internet. Education, careers, emotional resonance. If the result of that is that nothing matters, then why not be kind and loving?

The hopefulness of this film makes it an instant classic, no matter how modern and idiosyncratic it looks.

5. Aftersun

At 34, this is a prodigious directorial debut at Cannes, by Charlotte Wells.

Fully well-deserved.

This is a film that innovates both in its technique and in its thematic resonance.

A scene doesn’t go by without either showing us a thought-provoking frame, and/or gripping us emotionally with a build-up that reminds us of our own human condition.

Charlotte Wells is not being explorative with her camera in hopes of breaking new ground photographically. Every time you notice a creative way to frame a scene or compose a moment, it immediately makes sense with the mood we’ve come to with the characters and story. And, it’s as if the moving images are also propelling everything and everyone to the next memory in life.

Additionally, “Under Pressure” by Queen and David Bowie is a needle drop for the ages.

Aftersun has a year’s best performance by Paul Mescal, portraying a young man and father with a pained existence. In contrast to what we should expect, this is not a voyeuristic examination on those who are psychologically tormented.

By being rooted in emotionally autobiographical motifs, the film is more about those who have to come to terms with the impotence of not being able to help dear ones aguishly depressed. It tests us (and the filmmaker) for the possibility that in sadness (and even despair) there is subconscious learning, strengthening and growth.

And, if these elements of human connection are indeed strong and genuine, despite the agony of one and the impotence of the other, there will be ground for the purest and most impactful happiness of all of their lives.

4. Nope

There are so many things I love about Nope:

- The music by Michael Abels is the best of the year;

- I will always regret not going to an IMAX screening of the film, since Hoyte Van Hoytema’s cinematography is jaw-dropping (particularly those night sequences shot during sun hours);

- Daniel Kaluuya continues to add elements to his craft that make him the #1 performer I most look forward to seeing again. Keke Palmer is magnetic to the camera – when she’s in frame, we can’t take our eyes off her. And Steven Yeun remains the champion of the insoluble presence – his characters are always so intriguing, not because they are exotic, but because we can’t quite put a finger on what is going on in their lives and what led them to this point.

All that being fact, the thing I most loved about Nope is its bid against its creator’s already legendarium.

Jordan Peele, since his directorial debut with Get Out, has garnered a following for refashioning the horror genre. Alongside Chris Nolan, Tarantino and (maybe) Denis Villeneuve, Peele is part of a very rarefied group of ‘auteurs’ that their name alone is enough to make people want to get out of their house and buy a movie ticket.

This is a relationship with audiences that I would imagine no artist would risk jeopardizing. And yet, that’s what Peele decided to do with Nope.

In just his third film, he’s already deconstructing his fans’ expectations. More interestingly, he is deconstructing the very industry that he loves and is an integral part of – cinema.

Nope is being marketed as a horror movie. Ok. But, this time, Peele is not using the doom and gloom of the genre as a vehicle for social commentary. No. He is literally speaking about our fascination (and obsession) with images (more, if they are moving), no matter how horrific they are.

The film, contrary to previous Peele’s but in tune with the vision for this, embraces set-pieces and big moments as storytelling motors. All incredible. And there’s one, in the middle of the third and final act, that’s ingeniously in the service of this crossing of ideas. Images as currency in an economy of voyeurism and/or as drugs in an addiction to exploitative memetics of control and class.

A TMZ paparazzi and a master cinematographer juxtaposed. Are art and commerce indistinguishable the more ‘civilized’ we become? Are they masks in a ball where people dance off their most primitive urges?

3. The Banshees of Inisherin

Despite being sold as a comedy, the new Martin McDonagh’s was the 2022 film that tried to reach deeper in the obscurity of my soul.

Yes, I laughed out loud, as McDonagh’s humour is totally my cup of tea (or pint of beer, to be thematically accurate). On the other hand, the Irish filmmaker had a plan. To use a tragicomedic character – Colin Farrell’s Pádraic Súilleabháin – to grill on the decree that proclaims geniality and kindness to be incompatible.

The more Pádraic questions the rule, the more you start to notice that you and McDonagh himself are finding something even more profound about how progress can be dehumanizing.

And from progress we arrive at a staple of his filmography and play-writing: mortality.

I think Banshees of Inisherin is the best silver screen rendition of a drama that clearly has plagued him for many years.

To plague, because Inisherin can be seen as a sort of a limbo where the existences (and consequent deaths) of its islanders serve as units of value on the large scale of human life. And there’s an element of time. The cinematography conveys it gracefully without superimposing: a land stuck in time, where both fogs and suns are never too saturated. Is it progress held back? Or is it the last moment when we still had our priorities right?

Priest: Do you think God gives a damn about miniature donkeys, Colm?

Colm Doherty: I fear he doesn’t. And I fear that’s where it’s all gone wrong.

The Banshees of Inisherin was the film that touched me deeper in 2022. It not made me cry (like others), precisely because the sentiment was so piercing and novel that I didn’t even know how to process it. It’s a kind of intellectualization of emotion that petrifies you.

Like Colin Farrell’s character, you learn as much from the answers you get as from the ones you don’t. It may numb you. It may surprise you. Or even anger.

In the end, you’ll probably find a calm in your spirit, and a certainty that we’re all going to the same place. So, let’s be kind to each other and enjoy the small amount of interactions we are afforded in a lifetime.

2. The Worst Person in the World

From a technical and cinematic point of view, this film is so breezy and inventive that anyone can fully enjoy it.

At the same time, if you are a Gen Xer or a Millennial, you probably never came across a more perfect rendering of the feelings life and society elicit in you.

Anders Danielsen Lie is Generation X through and through. The way he delivers three or four lines in this movie perfectly translates to other generations how good conditions and expectations averted an immense potential for disruption and a life fully lived.

And Renate Reinsve is a volcano. She’s looking at how modern society moulded and exploited Gen Xers to drain their life force out of them. She’s angry at that phony and shitty way of organizing things. And she’s erupting in all directions, burning the bridges of civilizational nurturing to better express her nature.

However, like a volcano, she takes a while in acknowledging she’s stuck to the ground.

As a millennial myself, I felt seen xD

Worst Person is a generational cry for never-ending experimentation, discovery and self-reflection, with an essential call to recognize the importance of being in communion with the World.

You can be a volcano, or shake the world around you. But, don’t forget that you are just one of many tectonic plates in movement. And, be ok with that.

1. Drive My Car

A masterpiece.

This movie will be taught in film schools and talked about for years to come.

It’s a masterclass in directing, writing and pacing. And has perfect music, perfect cinematography and perfect acting.

To add to this ironclad structure, its emotional core, of grieving more the flaws we didn’t know than the person we loved, is a journey that only a perfectly crafted film could do justice to.

The way the third act of this film uses all of its craft, art and narrative pieces to express a positive thesis on human quality left me hopeful for cinema and for us.

- Drive My Car

- The Worst Person in the World

- The Banshees of Inisherin

- Nope

- Aftersun

- Everything Everywhere All at Once

- Tár

- After Yang

- Top Gun: Maverick

- RRR

- Happening

- Broker

- Petite Maman

- Hit the Road

- All Quiet on the Western Front

- The Fabelmans

- Paris, 13th District

- Decision to Leave

- The Northman

- Avatar: The Way of Water

- Licorice Pizza

- The Batman

- White Noise

- X

- A Hero

- Prey

- Hustle

- The Menu

- Fire of Love

- Jerrod Carmichael: Rothaniel

- The Souvenir Part II

- Emily the Criminal

- Flee

- Kimi

- Turning Red

- Babylon

- Triangle of Sadness

- Bones and All

- God’s Creatures

- The Tale of King Crab

- All My Friends Hate Me

- Cha Cha Real Smooth

- Official Competition

- Bodies Bodies Bodies

- Argentina, 1985

- Sundown

- Catherine Called Birdy

- Saloum

- Belle

- Black Panther: Wakanda Forever