Why don’t people finish games?

For casual consumers of the medium the answer is simple: videogames are not passive. Many people don’t want more challenge when they come home after work. And that’s fine, not all hobbies have to be for everyone. At the same time, there’s a conversation to be had about accessibility options in games, since it is a bit ridiculous that so many people are shoved away from experiencing the worlds and stories created by these artists just because of entry-level mechanics.

But that’s a topic for another article. This time, I want to frame the review of Sekiro (and other FromSoftware games) around another question: Why don’t hardcore gamers finish games?

I finished Sekiro two months ago. It took me 1 month and 17 days to see credits, in a normal play-through with a full-time job. And I loved my time with it.

However, I am a sucker for medieval Japan and had the experience of Bloodborne and Dark Souls’ credits under my belt. I don’t expect many gamers to have the same passion for FromSoftware’s environmental design and animation-priority combat to endure the difficulty of Sekiro. It is a tough proposition, even for someone who plays enough games to make an informed Top 10 by the end of the year.

So, how do I articulate these conflicting sentiments into a review that is supposed to serve someone other than me, while still conveying that Sekiro ended up being one of my all-time favorite games?

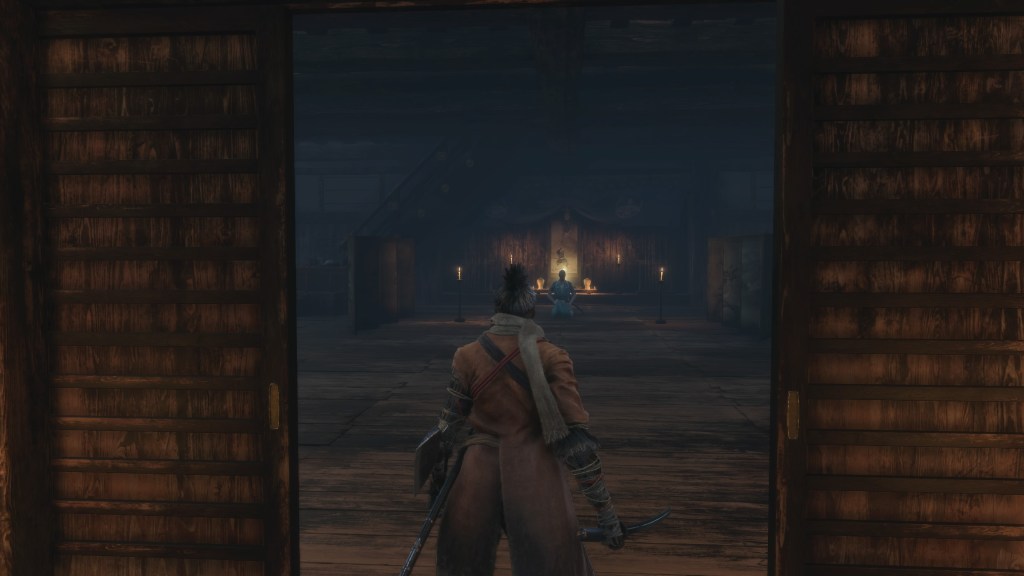

Like previous FROM titles, the game immediately got my attention with its visuals. This studio is not a powerhouse in terms of graphics’ technology, but the way their art conveys a sense of place and history is some of the best in the medium.

And since I’m very fond of the architectonic and cultural livingness of feudal Japan, I’ve been clamoring for a Hidetaka Miyazaki game in this setting for a while.

It lived up to my lofty expectations and then some. The interiors are decorated with sobriety and care, while the exteriors take you on a journey filled with interconnections and lore of different scales.

If you like the mythos of Japan, you won’t find a better rendition in any other audiovisual product.

Complementing this atmosphere, we have another majestic score by the up-and-comer Yuka Kitamura. I wasn’t as taken aback by this music as in her previous works, but mainly because this score is much more of a soothing undulation than the mountainous climbs of Bloodborne or Dark Souls III.

I wouldn’t call it minimalistic, since it ends up having more music than previous FROM titles, it’s just a more contiguous line of sound, instead of the intentional steep transitions between no-score to orchestral for bosses of those other works.

Thematically it also fits rather well, because this world has less horror elements and the bosses are more down to earth.

Additionally, it’s nice to notice some motifs of Kitamura’s previous compositions adapted to this different setting. It means she is beginning to have her own signature.

Then, comes the moment to pick up the controller.

And this is where Sekiro, despite its difficulty, hooked me.

I don’t come to videogames for their challenge. More than learning, I come to immerse myself in unattainable worlds, epochs and narratives in a way no other artistic field can: interaction.

So, more than getting absorbed by the technical aspects of how much I can do and its engineering fidelity, I care for fit and tonal consistency. There are a lot of games that have really ingenious mechanics and systems, and you can really embroil yourself in all of that tinkering, but if there isn’t an attention to how all of that connects with sentiments, expressions and lines of action in the game world, interactivity has the same shelf-life of a toy.

There’s a big difference between progressing in a game because you explore the limits of what you can do, or you explore the limits of where you can go. If a game is great at soliciting the first, but not the second, it’s very likely that a huge part of the player-base will never feel compelled to see in full what all those artists put forward with blood, sweat and tears.

And that’s why I think Sekiro is an interesting case study of this dichotomy.

It’s relatively consensual across gaming publics of different continents that FromSoftware has been the king of gameplay for quite some time. Still, there are a lot of hardcore gamers that buy these games, but don’t get enchanted enough to finish them. That says something of what really matters to us, as consumers of art, in the end.

Sekiro is no exception to this. In some ways, it’s FromSoftware’s gameplay opus. You are a shinobi known as Wolf or, more precisely, a one armed wolf: Seki (隻), meaning a one-armed person, and the second kanji, Rō (狼), means wolf.

If you want to role-play a ninja with katana skills as great as a samurai in a rendition of Japan’s Sengoku period, you won’t find a better feedback loop. Sekiro is animated with an astonishing attention to detail. You can either face your opponents head-to-head and parry with tremendous precision their varied attacks, or be stealthy and clear a whole section of bodyguards without their boss ever noticing.

And don’t be worried about his one-armed limitation. The prosthetic in its place delivers some of the coolest options for movement and combat, to the point of being designed with its own economy. This lends the prosthetic side of the feedback loop the right balance between crippling and special.

Like in previous Miyazaki’s games, even grunts can deplete your health gauge very fast if you aren’t paying attention. At the same time, and also like previous FROM’s titles (maybe even more), you are given almost all the tools to beat the toughest enemy from the onset.

I acknowledge that some Soulsborne fans might feel hampered by having to role-play with the same weapon for the totality of the story. But it is precisely this intentional constraint that allowed the designers to explore deeper and, importantly, more fleshed-out mechanics to how you interact with challenge in this world.

The fine-tuning facilitated by that self-imposed restriction made the gameplay loop always swollen and engaging. For example, in Sekiro, more than depleting a foe’s health gauge, you are encouraged to break his posture gauge and do a single deathblow. The animation and sound engineering are so pristine and conducive to the player’s inputs that even repetitive actions like parrying and deathblows always felt earned.

This was the constant fuel that propelled me to finish the story of this game, not its narrative. Which is noteworthy, since, like I said, I am much harsher with plot than with mechanics.

The story is not that great. While the lore and meandering narratives are very strong and it’s impressive how they inform the level design and overall world building, the main themes are already too much treaded. There are a lot of hardcore gamers that don’t dive that deep, and, in this case, wouldn’t get as much out of katana play as I did.

There are other systems that really compelled me to persist after each defeat. Not only I felt like I was growing after a boss beat me, because their attack patterns were (like mine) much more diverse and interesting than in Soulsborne, but also each victory was more meaningful since the only way to improve your vitality, posture and attack was by winning those special encounters.

This implementation of specialty for these moments when you, internally, are also heightening your state is *chef’s kiss game design. Fear of losing is rapidly replaced by force of will and pleasure in learning.

Still, this construct does generate fear of losing. And if you are not immersed in the livingness like I was, fear turns into frustration.

I find FromSoftware and Hidetaka Miyazaki’s games some of the best the medium has produced in the last decade. Their visual art and music have the perfect blend of dense and atmospheric. They control like butter. The loops reward you just the right amount. And the lore in their worlds and stories honor the explorers.

However, gameplay is not king. There are still a lot of hardcore gamers that will never experience all those artistic feats because a lack of a truly engaging narrative results in lesser motivation to overcome difficulty humps.

Since the release of Sekiro, FromSoftware has announced that their next game – Elden Ring – will have writing credits by George R. R. Martin. I wonder if this will prompt them to make a more accessible product to take advantage of the notoriety that such name brings to the table.