In terms of breadth, 2018 was not as great as 2017. For example, TEKKEN 7, the fighting game of this generation, was number 10 on last year’s list, but it would probably be number 3 on this one.

However, this year is so strong at the top that the first two games would duke it out for the crown in any year.

Still, I did not experience 10 games worthy of a ranking. That being so, this list will be structured as follows:

- 2018’s Old Games of the Year, where I will mention a pair of games not released in this calendar that I enjoyed;

- Disappointments;

- Respected what you went for, but it did not resonate;

- My Top 8.

I hope this makes the reading more interesting 🙂 . As usual, I will also give out the following awards: (i) Audio; (ii) Music; (iii) Visual Art; (iv) Technology; (v) Controls; (vi) Gameplay; (vii) Progression; (viii) Acting; (ix) Story; and (x) Direction.

2018’s OLD GAMES OF THE YEAR

TACOMA

From the creators of Gone Home, Tacoma is not as surprising as the first game of the company. It is, however, a better game.

In Gone Home you were mainly interacting with objects to move the story forward. While in Tacoma, its time-rewinding mechanic not only gives greater freedom and stimulates creativity to progress, but also lends an extra layer to the flow of the narrative threads.

If you’re like me and you’re a bit put off by the visuals, don’t be. They will rapidly make sense in the context of the plot and will even enhance the peculiarity of the scenario you find yourself in.

RISE OF THE TOMB RAIDER

Let’s be honest, the old Tomb Raider games did not age well.

So, when Crystal Dynamics decided to reboot the franchise, with Uncharted as a new reference, the change was quite welcomed.

The first entry, in 2013, did not impress me a lot, but there were some design decisions that showed promise, particularly the systems pertaining to exploration. And finally, a Tomb Raider videogame that controlled smoothly and had intuitive and fun encounters.

But, like I said, it did not leave me clamoring for more. Ergo, when Rise of the Tomb Raider released I gave priority to other games.

I should’ve respected the glowing reviews. ‘Rise’ truly is a big leap from its predecessor. Everything is better and, in some ways, even better than Uncharted.

All that marketing spiel about “becoming the tomb raider” is realized and intelligently fleshed-out in this sequel. The exploration systems I mentioned above really engage you in the narrative that Lara is just a rookie explorer trying to learn and survive.

You get the bigger chunks of Experience Points through discovering artifacts and tomb raiding. It’s really smart because you start to understand what moves Lara, what gives her strength. And through conquering mountains and monuments, her growing prowess when facing human opponents becomes less and less inconceivable.

More, the fact that you are encouraged (because the mechanics are satisfying) to approach those human encounters primarily through stealth, convincingly sells that Lara outwits her fragility and inexperience with all that learning she underwent in the exploration parts.

Despite the combat encounters playing really well, it is in the de facto “raiding of lost arks” that is the linchpin of this new Lara Croft – brains before brawn, insatiable for the dopamine that knowledge helps produce.

The story, set-pieces and production value are not as prestige as Uncharted’s, but the gameplay loop and progression tied to the archaeological aspects of Rise of the Tomb Raider make it a great game on its own.

Once again, I did not play its sequel, Shadow of the Tomb Raider, in 2018, and even if it was not Crystal Dynamics at the helm of that project, the foundations became so strong with ‘Rise’ that I will certainly find myself concluding the trilogy in a near future 🙂 .

DISAPPOINTMENTS

GRIP: Combat Racing

As you can attest from My Top 50 in this website, Rollcage is one of my favorite games of all-time.

So, when former developers of Rollcage announced years ago that they were working on a spiritual successor, it got my attention and climbed the expectations ladder, particularly because this sub-genre of combat racing has been dormant for many years.

I’m sad to say that Grip not only didn’t scratch that itch, but also disappointed me greatly. The game is not that good 😦 .

GRIP needed a little more time in the oven, so to speak. The developers at Caged Element nailed one of the most essential cornerstones of a racing game – the controls –, but you don’t get to enjoy them for too long because you are currently being interrupted by less than optimized design decisions.

Let me try to explain it. In Grip, like in Rollcage, you pilot very fast vehicles that are able to use that momentum and their big tires to continue the race from walls or ceilings. Ergo, transitions between the geometry of the track are the hook of these games. And, in Rollcage, they felt incredible. Chaotic, sure. But a well-crafted and controllable chaos that never contrasted with the overall sense of speed of the game.

And that’s precisely where Grip fails to recapture the mastery of its predecessor. Time and time again, I found myself colliding with geometry and going on a physics maelstrom that lost me time and positions in the race, instead of that same collision being an opportunity to test my ability in using the “grip” mechanic in order to maintain some speed.

To sum up, the race tracks (geometry, objects and architecture) are not well designed for the speed of the game, nor take advantage of the main reason you come to these games. And the solution, in my opinion, is not simply making the game a bit slower. No, I tried to drive slower and it was boring. The tracks, the collision and the physics need to be optimized.

DRAGON QUEST XI: Echoes of an Elusive Age

Yes, the music in this game is bad.

But, I could’ve continued playing it with Spotify in the background with a custom soundtrack made up of my favorite music from other JRPGs.

I couldn’t.

I played like 30 hours of it, though. But you really need to be in a particular mood to add more 60 to finish it. In a mood for game design and zany storytelling of a past long gone.

Dragon Quest XI is, unashamedly, a call-back to a bygone era of JRPGs. And I love me some turn-based role-playing coming from Japan. For years it was my favorite genre in gaming. But times have changed and genres can adapt without losing their core identity. Look at Persona 5, or even Final Fantasy XV (a more pronounced deviation). Both games released this generation and delivered very interesting takes on the formula.

This game has a simplicity in its aesthetic and message that is not charming or even adorable. It is unapologetically flat. A simpleton of a game that is putting too much trust on nostalgia and contributing very little to games in 2018.

I’m not totally opposed to the idea of going back to it and conclude the story. But I feel that there are a lot of better homages to retro nowadays than this.

SOULCALIBUR VI

Tekken 7 is the fighting game of this generation.

With that idea in mind, I hoped that VI was going to refresh SoulCalibur the same way 7 did to Tekken. They share developers after all.

It didn’t.

While Tekken 7 feels stacked with corporeal decisions that give shape to a modern fighter, SoulCalibur VI only showcases those same mechanics and systems without the understanding of how to make them gel.

The freedom of movement doesn’t have the proper weight, animation and sound don’t add-up to offer impactful sensations, and the music and visuals are very bland (even unintentionally cartoonish sometimes).

RESPECTED WHAT YOU WENT FOR, BUT IT DID NOT RESONATE

DRAGON BALL FighterZ

As a kid growing up in the 90’s, I know Dragon Ball like I know how to brush my teeth.

After getting to know other anime, I find DB a bit overrated. But, you always want to know how that old friend of yours is doing.

So, when Arc System Works, the best developer of anime fighters, announced that they were giving their spin at the franchise, I paid attention.

This game is not for me. It’s a tag-team one, and I don’t like those. Yet, ArcSys, by making the best Dragon Ball game ever, managed to keep me engaged longer than I expected.

The campaign progression is crap, but the controls and gameplay in each fight are so tight and gratifying that I wanted to learn how to get better. I found myself optimizing combos, and I am of the opinion that combos are more distracting than essential.

I completely understand if this game is in a Top 10 list. It doesn’t portray my tastes, but sure as hell is an important gaming mark left by 2018.

Ni no Kuni II: Revenant Kingdom

Opposite to Dragon Quest’s zaniness, Ni no Kuni’s simplicity and naiveté are charming and adorable.

This RPG by Japanese developer Level-5 is trying to use its aesthetic and gameplay structures to take an adventure to a nuanced intellectual place.

It doesn’t always succeed, but its cohesion keeps you engaged in the progression of the story and the interactivity.

In the end, it falls short of my Top 10 because I found it too easy for my liking, but I recommend it to anyone who enjoys the Studio Ghibli audiovisual experience.

MONSTER HUNTER: WORLD

This game served as my annual “Dark Souls in offline” campaign. And I know some of the criticisms I have against Monster Hunter World are precisely related to this way of approaching it.

I know that I found the Monsters too “bullet spongy” because the game was designed to be played with other people, mitigating the longer session for each hunt with conversations with your friends. And the same explains why I found the gameplay scenarios too repetitive.

You tend to excuse a lack of nuance when you are playing against or with other humans.

Still, the game managed to keep me engaged for 60+ hours and to see its campaign through. That has to count for something. I am not one of those people who spend that time watching a TV show to say it is bad in the end.

MY FAVORITE GAMES OF 2018

8 – GUACAMELEE! 2

Sometimes, more of the same is not necessarily bad.

Between July 30 and August 21 of 2018, there was a coincidence called the “Month of Metroidvania”, when long awaited games of that subgenre ended up converging to their respective release dates. Games like La-Mulana 2, Chasm, Dead Cells, Death’s Gambit and Guacamelee 2 all released within that period.

And even if I was the least curious about Guacamelee 2, on account of having played the first entry, in the end, it was the one I found myself glued to once again.

The sequel is not substantially different from the first game. But, the framework of systems and mechanics they created for the debut was so robust and intelligently varied that they can get away with Guacamelee 2 only being a refinement of that same framework.

The few times I sensed déjà vu it was joyous and not obvious. The rehashing was more like a rekindling of good memories.

Gucamelee 2 was more than my comfort food of the year. It made me appreciate even more the tight ship that DrinkBox Studios has in Guacamelee.

7 – UNDER NIGHT IN-BIRTH Exe:Late[st]

Another ArcSys’ joint (in collaboration with the main developers French Bread), this game has the intuitiveness of Dragon Ball FighterZ, but the focus of games like Guilty Gear or BlazBlue.

It controls so well that even grappler characters are fun for someone like me who can’t play them in other games. This game has a lot of complex systems, but the best tutorial in fighting games coupled with smartly designed procedures to execute them, makes the learning curve quite gratifying.

And as you can hear and see in the trailer, it has really good music and even better animations.

6 – OMENSIGHT

I am a sucker for a well-written detective plot. And videogames, due to their interactive nature, are the perfect medium to elevate the mystery-solving story.

It’s a shame, though, that there aren’t many good approaches to detective trappings in this artistic field.

The exception is Spearhead Games.

The developers behind Stories: The Path of Destinies and, now, Omensight, have found something special in their design approach to mystery-solving.

‘Stories’, despite some problems in its gameplay, narrative focus and overall audiovisual fidelity, showed some promise when it came to the use of videogames’ progression systems to enhance that essential element we all expect from a detective conundrum: hypothesizing the different scenarios.

Spearhead Games’ design doc lets you, the player, have agency on those events and, most importantly, gives state-altering consequences to those same actions. And, as soon as you understand how to use that to move the narrative forward, the progression becomes intrinsically linked to what you do on the “stick”.

Omensight is a more polished experience than Stories, and still isn’t the most beautiful of games. But this player agency to solve the mystery makes you subconsciously connect with the world, the characters and the story.

Only a videogame could do that.

5 – ONRUSH

Racing games are not among my favorite genres to play, because there isn’t, usually, much things to do besides, well, racing.

But, what about a game with vehicles, from motorcycles to buggies, where racing isn’t THE THING?

Hm. How so?

The answer is not exactly intuitive, and that’s precisely the genius of Onrush: the offspring of core ideas from MotorStorm, with Dota-like systems, and mechanics that worked for Overwatch.

The final product is an environment where I enjoyed some of the most entertaining gameplay loops in years.

It works. I don’t know what else to tell you. It works.

If you, like me, were tired of the lack of innovation in the racer genre. Give it a try. And even if you weren’t, play it. It’s so much fun and a breath of fresh air.

4 – Call of Duty: BLACK OPS 4

If there is one mark in 2018’s gaming that I should write on this page is the name Fortnite.

In 2017, the gaming world was surprised by an indie early-access phenomenon called PLAYERUNKNOWN’S BATTLEGROUNDS. I did not play it then, but I respected the design behind the Battle Royale formula.

Apparently, I wasn’t the only one, because Epic Games, the licenser of the engine in which PUBG was developed, blatantly applied that same formula to one of their in-house projects Fortnite: Save the World, a survival game with, now, a younger brother called Fortnite Battle Royale.

You probably noticed that, in 2018, Fortnite was way more in the zeitgeist than PUBG.

What makes Fortnite appealing to so many people are precisely the reasons why I never touched it. Still, I respect the battle royale concept a lot from a design point of view.

So, when, predictably, another big AAA studio decided to apply that same formula to one of their games, I peeped to see if I was finally going to experience a subgenre I admired from the outside.

Great, Call of Duty is doing battle royale. Even if I don’t like it, the package also comes with the traditional multiplayer I played years ago. (That was my rationale).

I didn’t even care for the lack of a singleplayer campaign. I used to buy CoD for two propositions, and I was doing the same here.

When the day arrived, like muscle memory, I went to the options menu to increase “stick sensitivity” to 8, and noticed that there was some kind of Tutorial. Cool, I haven’t played this series in years, it will be good for the rust.

Oh, this is where the “singleplayer in development hell” went to. Nothing major, but there are some high-budget cutscenes contextualizing each one of the Specialists you are able to choose in traditional multiplayer. And, more importantly, you also get training on their different abilities and the best situations to use them on.

Really neat. Multiplayer-only games should have a mode like this one, where we go through what the developers had in mind for that roster spot.

And it worked. After concluding the tutorials for all the Specialists, I decided to try traditional multiplayer before battle royale, and despite this new tactical layer of abilities, alongside the fact that I hadn’t played a CoD game since 2011, still, I never felt that the better twitchiness of habitués was preventing me from having a good time. All because the developers gave me a place and time to understand the utility and ramifications of all the tools at my disposal in multiplayer.

But the biggest argument I have backing Blacks Ops in my Top 4 is this: I still haven’t played battle royale. The traditional multiplayer is so good that it quenched my curiosity for BR.

I stopped playing CoD when Activision, in trying to prevent franchise fatigue due to unnecessary annual releases, started forcing changes to the experience that never looked earned but more slapsticked. And, more worrisome, seemed to forget what CoD was good at: fast reflexes, but grounded.

Ironically, Black Ops 4 has the best multiplayer since Modern Warfare 2 (2009), not because it is a “back to the formula”, but because it takes that formula forward with thoughtful takes on mechanics and systems from games like Rainbow Six Siege and Overwatch.

The reach of CoD has expanded. It has become more tactical due to the “Operators with different abilities in tight corridors” and more accessible/fun at the same time due to game modes and maps designed to serve different types of players, who will choose different specialists with different abilities to contribute to a match.

3 – THE BANNER SAGA 3

Five years ago, I was captivated by a vision: Stoic Studio’s for a Viking legend-inspired world.

If you like those mythological themes, just check that trailer and tell me you’re not enthralled.

As anyone invested in a subject, I had my head simmering with ideas and expectations for the realization of what Stoic was showing me.

And, at first, I was kind of taken aback by their take on the mythology. It is DIFFERENT, to say the least.

But, The Banner Saga is so expertly written that everything makes sense in this version of the viking lore. Stoic knows what the historical and cultural motivations behind the myths are and never loses those cornerstones. That, coupled with the confidence to never miss a narrative just to accommodate for external preconceptions of what ‘Viking’ is, makes the world of Banner Saga mythological on its own.

The Banner Saga 3 is difficult to analyze without referencing 1 and 2, since you always pick-up the next game moments after the previous has ended. The trilogy could be played as a single game and you would notice very few changes.

At the same time, this third entry in the series does justice to the narrative structure of culmination by introducing a new system to the overworld decision-making and a mechanic in the battle scenarios, both completely coherent with ending a story. Those interactive tools put the writing in check, making it better, and vice-versa.

It is one of the best realizations of converging a multi-part adventure that started years prior that I’ve ever seen in any medium, and the innate characteristics of videogames enhance that same feeling of closure.

2 – GOD OF WAR

“First impressions matter” is a saying that is as true as it is dangerous. As matter of fact, its dangerousness emerges precisely from its trueness.

Many times, artistic endeavors are so focused in grabbing your attention from the get-go and stamping impressions near the finish-line that they end up feeling more canonical than expressive. There’s nothing wrong in wanting to take your audience on a ride; the problem is that a roller-coaster is made of unbendable material, while a plot should be organic like the source it comes from. Narrative threads should be exactly that: threads that weave around you, and if there is contact, you feel enfolded by them. Storylines and acts are not legos.

So, I became instantly afraid for God of War when I was presented with such an impactful and well-paced first hour. How can they top that?

Boy, they top it. From adventure thrills, technical amazements to emotional stakes, this game is a beautiful tale that puts its arm around you and shows you its world.

All these months after seeing credits, I still find myself nodding in respect for how the development team at Sony Santa Monica managed to so tightly enrich a self-enclosed journey with such grand fantasies, explicit or implicit. Damn, they really scaled everything in reference to that pace and tone of the first hour, without ever losing nuance, swings or intrigue. Bravo!

It goes without saying that a lot of talented and ingenious developers worked on this game, as beautiful ideas and visions keep surprising you in every corner. Even so, I have to put the spotlight on the person behind the majority of the Yes’s and No’s.

I was hoping to save his name for later, since, besides all the other developers’ own personal and emotional contributions, it has been quite clear that this work syphoned a lot of intimate energy out of its creative director. And for that, you have my eternal gratitude Cory Barlog.

Saying No to a good idea because it doesn’t gel with the bigger picture, or saying Yes to a vision when there’s tremendous risk associated with its transformative contagiousness is a path that requires a lot of mental fortitude and belief .

And God of War must have been as big a headache to direct as it was enjoyable for Cory. From its mechanics, systems to engage with, modernized gameplay loops or even the mandate to not do camera cuts, all had their unique challenges, the bigger being the coherence between all the parts.

Cory and the team nailed it.

Having a game of this scope that achieves a degree of communication between gameplay, progression and story is so rare. Usually one element suffers or is dissonant. Not here.

To contextualize, you play as Kratos, the former Greek God of War, and his young son Atreus, and following the death of Kratos’ second wife (Atreus’ mother), they journey to fulfill the promise of spreading her ashes at the highest peak of the nine realms of the Norse world. Kratos keeps his troubled past a secret from Atreus, who is unaware of his divine nature, but, along their journey, they will encounter monsters and other gods.

It is incredible how the game keeps giving us human resonance through the sober beauty of this simple premise. When credits rolled I was stunned by the elegance and care of how the plot explored and developed these narrative themes.

Adding to this artistry, there are gameplay loops and systems that not only are a blast to interact with, but were also carefully designed to be logical with the themes being explored and transmitted by the game. Kratos is foreign to this land, Atreus is still learning about the world and both have different things to teach to each other, in combat and in exploration.

The progression does not use the story as a device to move things along. On the contrary, you sense that the story is moving because of the “leveling up” you did through gameplay. Their relationship with the world and with each other evolves and, as such, you get to see them interact in a very organic way through cinematography.

There’s never a disconnect when Kratos evolution is represented by new moves and techniques to a foreign weapon (Leviathan), or collecting trinkets to upgrade it, because the upgrading has to be done by characters of this new world and not by him. He also gains experience through fighting the same enemy more than once, or exploring the environment, because Atreus has all the myths and lore about these monsters and epic ancient battles and gods engraved into his mind, which makes perfect sense. When I was his age I dreamt awake of these fantasies.

Atreus’ presence is also smartly designed into combat. First, you have a dedicated button for his actions, which not only creates a literal physical connection with this character, but also makes it clear what’s the hierarchy in these situations: Kratos has more than 6 buttons at his disposable, Atreus only accounts for 1.

Still, this doesn’t mean that Atreus is secondary to combat; quite the opposite. By choosing a very close over-the-shoulder perspective during action, and with increasingly more varied combat encounters due to the exploring of lands and realms with their own battle lore, it is not unusual for Kratos to become surrounded by enemies that can only be beaten with a particular technique he’s just learned. So, to get a time window to think and execute the new tricks at his disposable, it is vital to use that Atreus button to attack those enemies that aren’t in your field of vision.

This is a prime example of how videogames can establish a relationship between characters through challenge and interactivity.

I must admit I was on the fence about the decision to change the camera perspective from God of War “classic” to this new one. Not because I had anything against this style, but because I’ve had been witnessing a lot of franchises abandoning that more distanced positioning, which has generated so many memorable moments in terms of choreographed vistas.

After a few minutes in, you know why the team led by Cory Barlog made that bet. It makes so much sense thematically: You are moving forward in this journey; it is paramount to always see Kratos’ back even while exploring; he is doing his catharsis by moving forward but his back is still heavy with burden. And if you notice how Sony Santa Monica handled the grandeur of mythology this time, it also makes sense why the camera is so close to our characters. Myth and lore are treated as cultural heritage, as ever-present fears and dreams that change our vision of the world, but through introspection. Whereas previously, gods and monsters were front and center. The notion of play in games was still very attached to objects and bodies.

As the medium evolves, we get a new offer: play with thoughts.

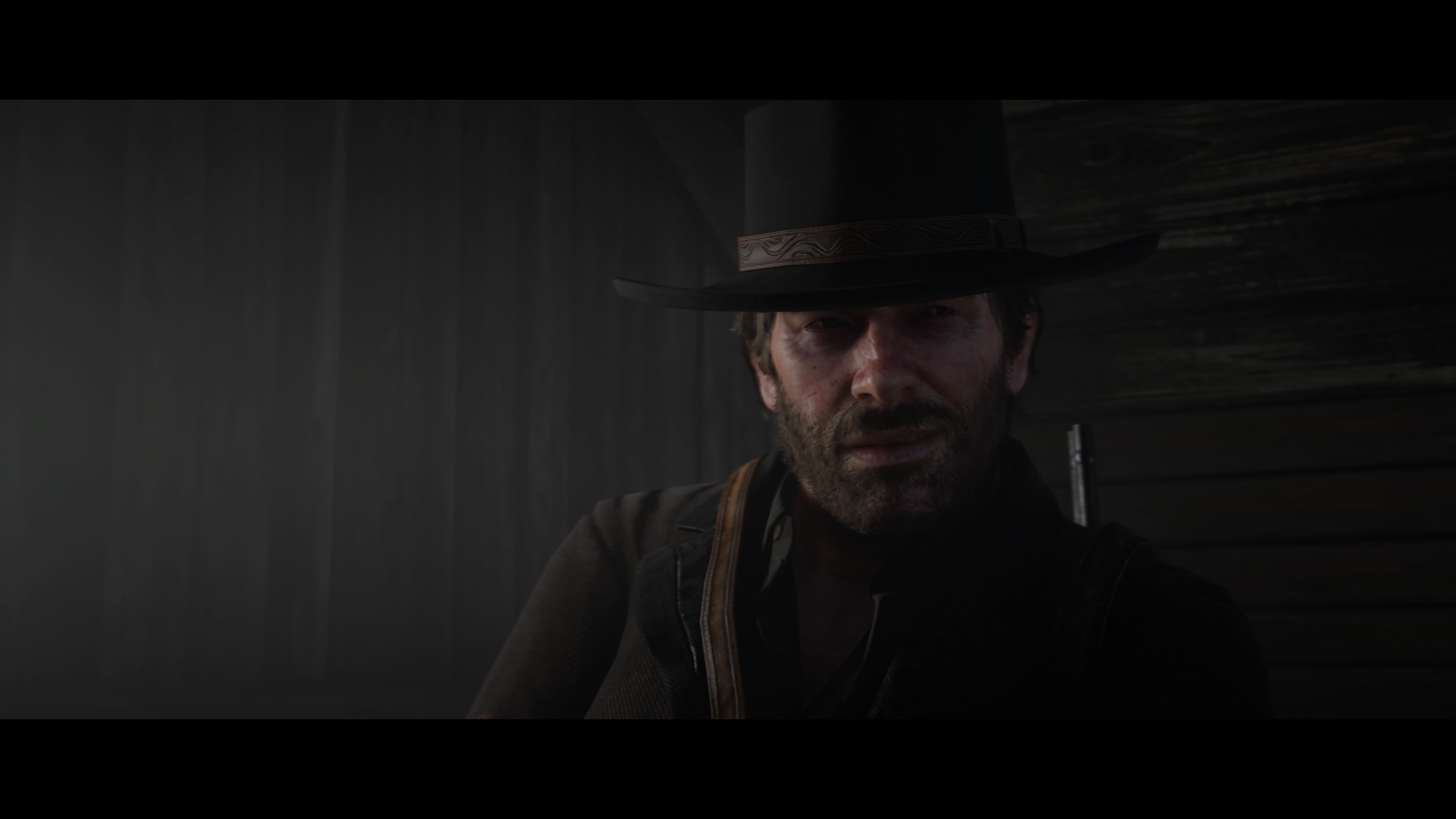

1 – RED DEAD REDEMPTION 2

Almost 20 years later, I might have found the game that surpasses Final Fantasy VIII as my favorite of all-time.

Red Dead Redemption 2 is, certainly, the best game I have ever played.

Videogames are the poster child of the instant gratification era. So much to play, to experience, to entertain. Always thinking of what’s ahead, burning through our current distraction, with the fear of missing out.

How many people actually finish what they buy?

That is one of the reasons why game design is still, for the most part, too enamored with the playground framework, where mechanics are inspired by toys and systems reference competitive sports.

The majority of developers are rightly afraid that if their vision for interactivity is not complemented with health meters, gauges, scores, timers, collecting shiny things out of foes, all full of color, fluid movement and loud music, the senses of the player won’t be totally occupied and, as such, not completely engaged.

Through this design philosophy, games tend to become arenas of entertainment where the gladiator in you heroically, otherworldly and smoothly punches, jumps or interacts with objects, making the emperor, also in you, have fun. Players become immersed in the toy box.

Gameplay can be much more than that.

And that next level of game playing was precisely what the Rockstar Studios sought to reach in their new project.

They accomplish this with such an uncompromised vision that Rami Ismail, one of the most interesting voices in the developers’ community, said (paraphrasing) that Red Dead Redemption 2 is the most expensive indie game ever created.

I completely agree. Remember when people criticized the first RDR for having some slow-paced moments, or having too long animations (like skinning) for the likes of a videogame? This is the same team that makes Grand Theft Auto. “Imagine if they mandated stopping on traffic lights.” (People said).

After RDR 1 they made GTA V, not only the most arcadey of GTAs, but also the most successful audiovisual product of all-time.

It is therefore ridiculously impressive that their vision for interactivity in 2018 (eight years after the first RDR) was to scrape off the majority of what made GTA V a captivating success, and double-down on those criticized concepts of RDR1.

There is no other team of game developers in the world that can pitch to a public traded company like Take-Two Interactive the theme of the gameplay and story of RDR 2 and get money and five years of exclusive work from 2.000+ people in England, in the United States, in Canada and in India.

To all the courageous visionaries, artists, the people who put their sweat and soul into this endeavor and the ones who believed and invested in this choice for the interactive experience, I thank you. You gave me gameplay so immersive that I lived your work, your world, your passion, your message with an engrossing feeling that I have never experienced in games or other medium.

One of the best examples of the theme chosen for this game can be noticed through the collaboration of the Audio and Music departments.

Woody Jackson, the composer of the game, made a phenomenally varied soundtrack, with more than 100 tracks, since there are 109 different missions and each one of them as a different tune, alongside some more entries for when you are exploring the world.

The score of the first game was already really good, not being overshadowed by giants of the genre like Morricone. But this one?! It was crafted with an intelligent expressiveness that never loses its heart. From minimalist approaches that embrace the natural environments, to bulky rhythms and strings, different genres of those sides in different regions, and even the vocal tracks, powerful or somber, always hitting the right moment.

Still, what impressed me the most out of those 100+ tracks was the magically hidden scripting of silent moments.

I was riding my horse through a forest with some of that not in mission music, and it started raining. After 10 minutes it stopped, and the woods were completely silent for a while before coming alive again.

This carefully crafted scenario, seemingly procedural, is counterintuitive to the tenets of play. It’s not fun, it’s not entertaining. But I would argue that rewarding a player with moments like these, without the need for meters, gauges, scores, shiny things or loud music, and solely through a coherent on-the-stick experience where audio, visuals, controls and narrative cornerstones completely gel, is the next level of gameplay in this medium.

Another example of why I admire tremendously what Rockstar went for in this game can be seen in the Visuals.

Red Dead Redemption 2 looks incredible, and impressively runs without drops throughout the entire world, while looking great. But more than the technological aspect of it, what really got to me was their take on photorealism.

They clearly had the means to go photographic, but they chose to go cinematographic. I.e., they could have gone full simulation on the cowboy experience and times, but they opted for an aesthetic that exudes our idea of what The West was.

The art department, led by Aaron Garbut, directed the palette of colors, the natural light of sun and moon, the human-made campfires in the wilderness or candles in the cities, as well as the volumetric effect given by mist, industrial smoke, trees in the wind, deserted prairies, snow, reflections in the water or even the impactful presence of a house or a store, all in a way that transmitted the ideals and metaphors of this game respectfully to your imaginarium.

I felt free in the wild, like a pirate at sea, and a fish out of water in every city I visited. They were able to craft contours, shadows and geometry differentially to make me feel this way, without ever losing the overall aura that this game needs to support its narrative.

By now you might have noticed that I’ve been praising the gameplay of Red Dead Redemption 2. A part of the game that didn’t click for some people, which I completely get. After all, Rockstar’s vision for RDR2 is not fun.

Art isn’t always fun. Some is, but other isn’t, and what matters is how engaging it is. I bet a lot of people who bought RDR2 didn’t know what they were getting themselves into, after having played GTA V or the majority of other open-world or action-adventure games.

For starters, Rockstar’s design philosophy and its realization in the environments, mechanics and systems goes so coherently strong in one uncompromised direction, that makes what is, conventionally, an action-adventure, the best Role Playing Game I have ever played.

I’ve heard people complain about the controls – that they are laggy and slow. I never felt that. Red Dead’s presentation, set design and dynamics are so deliberate and fulfilled with nuanced opportunities and lines of action that I found myself walking slowly when it fit the context, or being the “best shot” in the gang, twitchly gunslinging when needed. And the feedback on the stick in both scenarios had that type of contextual precision that elevates the immersion in the events on the screen.

In terms of the typical playground framework of games, RDR2 is built on 18 main systems:

- Health;

- Line – gauges the physical damage you can sustain at any moment;

- Core – governs the rate at which the line decreases.

- Stamina;

- Line – gauges the amount of physical exertion you can do at any moment;

- Core – same idea of health core, but for stamina.

- Dead Eye;

- Line – gauges for how long you can slow down time;

- Core – same concept.

- Horse;

- Health – with line and core, and with the same principles;

- Stamina – also with line and core;

- Bond – governs how much you can maximize your companion’s potential, and how much it trusts you, changing its behavior.

- Money;

- Camp;

- Money – funds separated exclusively for buying small useful constructions and supplies for the camp;

- Provisions – you and other members contribute to the pot, and then you can take them for a cheaper price than on stores;

- Medicine – same economics as provisions;

- Ammunition – same logic.

- Wanted – when you are a bad boy, if there are witnesses and they report back to the law, you get a bounty on yourself.

- Morality – from big to small acts, all is registered in this meter, leading to meaningful differences to your interactions in missions throughout the game, and even the ending.

It might seem hard to follow, but Rockstar had such confidence, not only on the activities they created to engage with those systems, but also how they designed the flow between them and the aesthetic and narrative contextualization for each one, that they hide in pause menus the “numerical” effects of the current systemic status.

I found myself drinking coffee not because it gave benefits to my Stamina Core, but because the sun was rising. I ate dinner not because it replenished my Health Core, but because I wanted to be at camp at night listening to non-mission conversations.

I smoked a cigar when pinned down to a corner in a shootout not because it gave me more Dead Eye, but because it was badass.

I fed, brushed and patted my horse not to increase its health, stamina or bond stats, but because we shared the same ludonarratives and adventures in that land.

I donated money and other supplies to the camp not motivated by profit in the margins, but because its ambience, the fleshed-out personalities and my relative position in theirs and our story made me feel at home.

And finally, my morality gauge progressed the way I perceived my Arthur Morgan at each juncture, not gaming the system to gain or unlock something, but making decisions that felt aligned with the connection I was establishing with Rockstar’s writing for Morgan and Roger Clark’s (the actor) rendition of the same. Right or wrong, this type of human relatedness, found in other great pieces of fiction, made me role play Arthur to such a profound level, that everything, good or bad, happening in front of us (me and him) made sense.

If this is not the next level in gameplay, I don’t know what is.

I hope it has become clear that I find RDR2 to have music full of heart, visuals permeated with allegory and gameplay enhanced by a deliberate embodiment of character as fully realized as I ever seen.

Still, there is an extra level of greatness: its narrative.

The year is 1899, and the age of the cowboy and of the Wild West is ending. In this context, the Van Der Linde gang plans one last major bank robbery to set them for life. However, said heist goes wrong, with several gang members dead or captured.

I love how this game starts. You come into the scene as Arthur Morgan, Dutch Van der Linde’s most trusted lieutenant, not having witnessed, as a player, the heist or the deaths of your companions, but you know Arthur and the rest of the gang lived through that. From the get go you know RDR2 is not about showing you drama without being earned by the player.

Even older stories of the characters’ lives, that are an important theme of the game, are respectful to the present the player is living. The writing team, led by Dan Houser, knew how to show you where these people came from without using the easy road of predetermined dogma or destiny as a lesson. No, these characters are a product of their past AND present, with actions AND reactions intermingled to make you pay attention.

That’s why I love Arthur Morgan so much. He has an arc that makes sense every time. Like traditional game mechanics would hinder how you find yourself inhabiting that place and time and embodying that character, traditional plot devices are not the reason why Arthur changes. You don’t feel cheapened by something different out of his mouth because it is as important to Rockstar to show you the smallest reactions as it is to present the big actions.

Many game developers are afraid to give protagonists this type of arc because, contrary to movies or books, you are in control. Then again, the way Arthur carries the themes and message of this game and expresses them, not as a recipe, but organically, demonstrated how to give life to an individual that thinks and acts about his role and mission in a game world.

Red Dead Redemption 2 is the first game triggering, for me, that same sensation you have when you are reading an engrossingly written book or watching an involving movie and, suddenly, you are there. Truly there. You know there is a screen between you and that world on the movie, or even when there are no images or sound, like a book, an object composed of pages, and yet, you find yourself crying. One of the rawest human instincts, there, uncontrollably falling. Why?

That reaction isn’t metaphysical or spiritual. It is, in its essence, a product of empathy towards other people’s pouring their truest expression, their human feelings into the craft of art.

I know this is a game, a virtual world with dissonant idiosyncrasies. Why did I find myself THERE?

Precisely because IT IS a game. The interactivity, my agency, framed in a deliberate aesthetic rich with both scale and detail, stimulated those sentiments even more than a book or a movie. The breadth of gameplay moments, all weaved together to support the message of this story, made me fully inhabit this place and embody this character.

I lived Arthur Morgan’s life. Game playing turned into a natural day-by-day with and within him. In his head, planning out his actions and journeys. It came to a point when I didn’t even notice traditional game systems like upgrades, icons on a map or mission markers. I didn’t choose between exploring the world and doing a mission because of game logic. Everything about how the world interacts with Arthur and how he interacts with it made those choices more like sentiments than game flow.

So, when drama occurred in his life, I felt it.