The Courage to do Nothing

Remember Lost? The TV Series that started as a thrilling mystery involving a plane crash on a seemingly deserted tropical island, and by the 6th season had mutated into a discombobulated religious allegory. Despite the general disappointment towards its culmination, the hook had stuck. TV finally grabbed the attention of mass audiences as a platform for long-form cinematic storytelling, and those same viewers were left craving for more. Lost was one of the biggest catalysts of the times we are living today, when accomplished movie directors, writers, actors and even cinematographers are looking at TV as a fruitful environment where their art can be respectfully exposed to curious and critical minds and not only to couch-potatoes.

There were series better received by critics in years prior – The Sopranos (1999) or The Wire (2002) – but it is undeniable that the structure designed by J.J. Abrams, Jeffrey Lieber and Damon Lindelof struck a chord with millions of viewers. It was more ambitious than a crime drama. It had a diverse cast of characters dealing with something that resonates with everyone: working together towards survival. And it was sprinkled all-over with mystery. Arguably too many sprinkles to feasibly tie together in a narrative that could always ground itself in a modern set of rules, and not end up being another one that resorts to Deus Ex Machina to solve its converging problems.

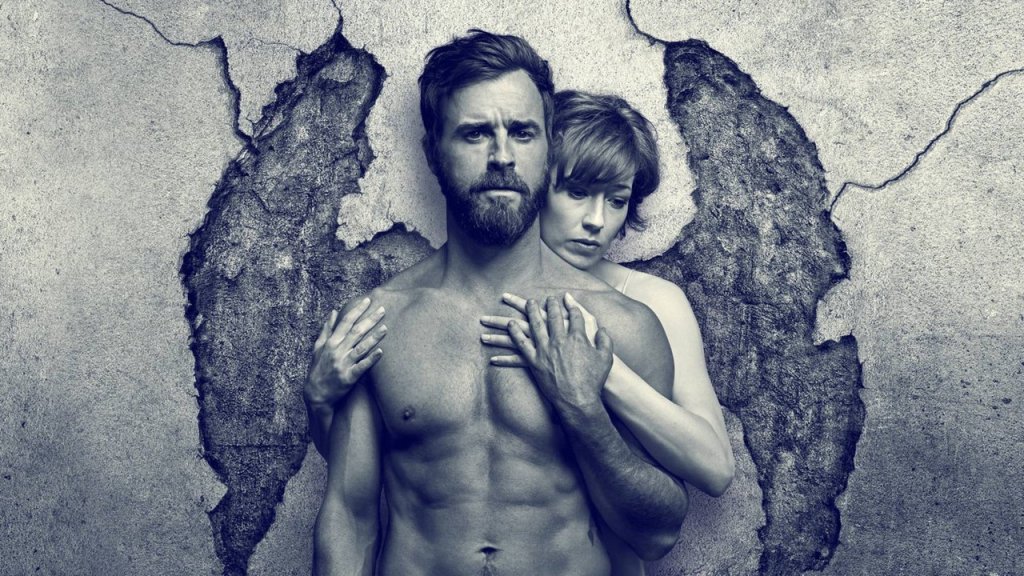

The Leftovers is the anti-Lost; in so many ways. Yes, Damon Lindelof is also its show-runner. Yes, it is designed around Human Drama, Mystery and even Fantasy. And yes, it also has a diverse cast of characters dealing with a very close-to-heart event. Yet, these characters are way more nuanced than the ones in Lost. The complex themes they are faced with have meticulously written cornerstones that, when push comes to shove, treat the audience towards intellectually mature conclusions. And, probably the most differentiating factor, The Leftovers is not a series watched by millions. That weight was too much for a generalist production/broadcasting company (ABC) that was not connected to the artistic vision from day-one and ended up being a bad influence to the last seasons of Lost. No, this time, Damon Lindelof had a nourishing environment to work in – HBO – and him and his writing partner (Tom Perrotta, who is the original creator of the story) were able to tie-up all the loose ends in impressively sophisticated ways.

This series is divided into 3 seasons. The first aired in 2014 and, more interestingly, the last one aired in 2017. The gap was between season 2 and 3, where the show-runners had a full year to build a very difficult to land last season. That time was put to good use.

Production clearly ramps up from season to season. Usually related to money, this also was vital towards conveying one of the central ideas of the show: even if you try to change your context, your brain comes with you; so, you have to deal with it first.

The first season takes place in the fictional town of Mapleton, New York, where a group of people struggle to continue their lives after the sudden and simultaneous disappearance of 2% of the World population (~140 million people). The next two seasons introduce more places and characters that live there.

Despite some changes in locales and even timelines, the production always had their eyes on the small details of every-day life. It was essential for the intimacy cornerstones across episodes that attention was given to interior shots. The way homes were furnished, utensils placed or the juxtaposition between in-house clothing and work attire, all add up to a set texture that showed personality when the characters could not, due to coping with the unexplained tragedy.

Additionally, there are some out-of-left-field episodes that are intended to be very stylized, and the production team helped the director and cinematographer tremendously by creating the costumes and makeup appropriate for the tone being filmed.

Where there’s fiction, there’s a visual effect. In The Leftovers, the crux of the premise is undoubtedly fictitious, but it is the minimalist use of visual effects that give it the extra punch. It’s fantasy, and yet it feels so real. This closing of the gap between the supernatural and the tactile is what makes you connect with these characters. You start to understand what they are going through. You sense their emptiness because the vacuum is right there. And when some unrealistic effect was to be revealed, they never felt untimely or superimposing, which lead to even bigger audience-character empathy. We were all trying to solve this mysterious event.

Then again, there is another artistic contribution that tends to smoothen out the connection between receiver and claimant. And that’s music. Let me tell you, this series has one of the best scores of all-time TV. Most certainly because it is composed by one of the biggest geniuses of contemporary orchestral sound – Max Richter.

The West German-born British composer is the perfect fit for the message being conveyed in this series. His minimalist style is so incredible that is able to encapsulate in the simplest motifs a myriad of conflicting feelings like sadness, courage, faith and rationality. I was really blown away. Also, Richter is never afraid of finding a common ground for pop and classical music, and from that dialogue rise the most astonishing melodies that accompany beat by beat the visuals on screen.

If the soundtrack snuggles the show amongst the quality HBO has accustomed us to, the combination of acting, writing and directing catapult The Leftovers to the mountain of the greats.

I’ve talked a bit about the writers, so I’ll leave those for last. First, let me introduce you to the highlights of the cast: Justin Theroux plays Kevin Garvey, Mapleton’s Chief of Police, and father of two who is living the breakup of his family since his wife, Laurie Garvey, played by Amy Brenneman joined a mysterious cult called the Guilty Remnant. The leader of the local chapter of the cult is played by the wonderfully sober Ann Dowd and, in my opinion, brings about an even better performance than the one in The Handmaid’s Tale (2017). Liv Tyler is also connected to the cult storyline; she plays Meg Abbot, a woman about to get married that suddenly becomes a target of the Guilty Remnant. This is Tyler’s career performance.

Three more names have to be mentioned, since two of them are among the best acting in the series. Those two play sister and brother: Carrie Coon (the #1 performance in the show) plays Nora Durst, a woman who lost her husband and two children in the Sudden Departure, and Christopher Eccleston, who plays a former reverend having trouble grasping the “Christian” meaning of the event. The third actor that should be referred is Kevin Carroll. He only shows up in the second season, but is a big reason why that’s the best season of the three.

All these amazing works have to be thankful for the team of directors accompanying them. Shows with this scale usually have several directors, in order to lend some uniqueness to the different episodes. The Leftovers is no exception, and in spite of having 10 different directors for 28 episodes, I can’t remember an episode where quality fell below the very high standard of the three seasons. And that bar is set by one particular director: Mimi Leder. The first female graduate of the AFI Conservatory (1973) directs 10/28 episodes. And they are astonishing. They really demand that I don’t refrain the hyperbole: some of the best TV episodes I’ve seen in my life. Her past studies of cinematography are evident, because the “Leder episodes” were full of sensible close-ups. Every time the frame focused on an actor, Mimi and the cinematographer were not forcing intimacy. They would converge towards the performer but would leave them the right amount of space to perform. The story was not being bullied-out of the actors, instead, the film-crew directed by Leder were giving the actors a comfortable embrace for them to feel safe to express the abstract concepts that are at the core of the series. It really was one of the best collaborations I’ve seen between actors and director.

Another name that should be highlighted is Craig Zobel. He only directs 3 episodes, but you will remember them. They are very contrasting episodes to the ones from Leder, and from the general tone of the rest of the series. However, their whimsical is properly placed throughout the seasons and always punctuate like a semicolon and not like an exclamation mark. One of those episodes is the best in the entire show.

As promised, now it’s time to dive deeper and give praise to the work of the writers. Like in the Directing department, the writing credits encompass two digits of contributions. I shall center my attention on three names: Damon Lindelof, Tom Perrotta and Nick Cuse. The first two are the series creators and worked on all 28 episodes. Nick Cuse is not only the following writer involved in more episodes (11/28), but he’s also present in some of the most memorable ones.

Let’s start by addressing the elephant in the room. No, The Leftovers is not another religious allegory like Lost. Religion is obviously an important theme of the plot, since, well, 140 million people suddenly vanished out of thin air. But that’s it. The message being conveyed is clearly academic, either from the perspective of emerging cults like the Guilty Remnant or the views of the former reverend portrayed by Christopher Eccleston. More, his sister in the show (Nora Durst) is one of the reference points for the narrative flow because, despite having lost husband and kids, she is first and foremost a rational thinker, and the answers she is seeking are only respected if their roots stem from Science. The writers give her (and us) that.

Conversely, the most important theme of the series is not the analysis of which force compels us to obtain clarifications about the unknown, but rather, more innovatively, to have the courage to do nothing. A journey to shake off the cilice that demands answers, even if they are intellectually easy. A process of diluting egocentrism, not due to fear of the supernatural, but originating from societal relativity and natural empathy. The story of The Leftovers triumphs where Lost failed because the answer is not “God”, the answer is “Human”. You will not be disappointed with the culmination of each character because they were the ones who chose the road to travel on. It was not pre-ordained.

Finally, I should talk about the Editing process. For several reasons, this was also a victory for the show. It’s not a very long series, yet, it has a bigger main cast than what should be expected for its length. I bet it was difficult to juggle between them in a way that could give them time to flush-out their remarkably nuanced personalities. David Eisenberg and Henk Van Eeghen (two main editors) did impeccable work on scene transitioning and constructing 1 hour long episodes that respected what each character was bringing to the table in that juncture.

Also, the montage was able to support one of the most fascinating traits of this series: tonal shifts. The show is structurally balanced: 10 episodes + 10 + 8. Even so, the three seasons are artistically realized as three different pieces. The first season is a thriller, the second is a crime drama and the third is an essay. All sharing characters and storylines. That structuring is visible due to the work of the production crew, cinematographers and directors, but it’s still really cool to see that the editors ended up joining those pieces in a coherently beautiful landscape puzzle.

The third season of The Leftovers is the best show of 2017, and one of the best series I’ve seen in my lifetime. It’s short (28 hours), but it’s not easy to see. However, that difficulty does not come from production flaws or unreasonable writing assumptions. You will feel awkward because you are not used to this type of approach. TV, by its very episodic nature, has to give something back each tick if they expect the audience to return next week. The Leftovers takes a long time before they feed your pavlovian urges. I was about to give up on it mid-first season, especially because I knew it was co-created by someone who had co-written Lost. Then the hook stuck! Those characters, the performances giving life to them, Mimi Leder’s directing, and even Max Richter’s score were trustingly pushing me towards the screen, like a book that has flying pages.

I can’t recommend it enough. It’s an ode to the environment TV can provide that Cinema can’t – a longer format tailored to character development. Watch The Leftovers with a mindset that fast-food answers is not what it is being served, and suddenly you will find yourself caring for those people. The writing is that good. Lindelof, you’ve done it; you’ve erased that weird taste from Lost. Kudos, sir.

This series is HBO-grandiose while it’s clean of all bells and whistles one might expect from its premise. It is in that intentional removal of sparkle where the show finds a placement for its tone. The gracefulness by which the story-threads are pick up and walked towards their destination is hypnotizing. And, in the end, when you are confronted with its message, you do not feel patronized by some high-and-mighty life doctrine. The message speaks the same language as you, because you have been learning that language alongside the characters. It makes sense.